The Bevan Briefing #9 - PFInally it's happened to me.

I regret to inform absolutely everyone that I have been having some thoughts. Notions some might say, about the news that, like a lot of things from the 90's such as the Gallagher brothers and posh spice potentially being problematic, PFI is back on the cards.

I have stomped around thinking there has to be a better way to fund hospitals (and other big capital investments like EPRs). So I did what any self respecting analyst would do and I made a database with 15 million data points in. I pulled together all of the NHS provider accounts for the past 10 years and started to poke about.

I am very happy to share this data but it's too large to opensource on GitHub so if anyone has any other ideas then let me know. It's in a DuckDB file. And it's large...

It sadly proved me right that PFI is an ABSOLUTE SWIZZ. I knew it was shit but my gosh when you pull the financing costs against the ERIC returns on the backlog costs it looks super shit.

I have therefore gone to town and written all about why it's bad, but importantly what we can do instead by looking at what other countries have done as well.

I propose an NHS Infrastructure Bank which could fund things at a competitive rate whilst getting some of the programme economies of scale which have been fumbled previously.

Anyhoo it's quite the tome and nutrient dense because it's important we get this right - the implications for the health of the nation for the next 30 years kinda depends on it so this one is quite research heavy. You are likely to need caffiene. I certainly did.

The references are on a separate page, quite frankly I ballsed it up a bit this week. I asked AI to help a sister out and, like most AI's it did not help a sister out, it made things worse. So it's now just my notes on a separate page.

The NHS Capital Crisis: Another way out

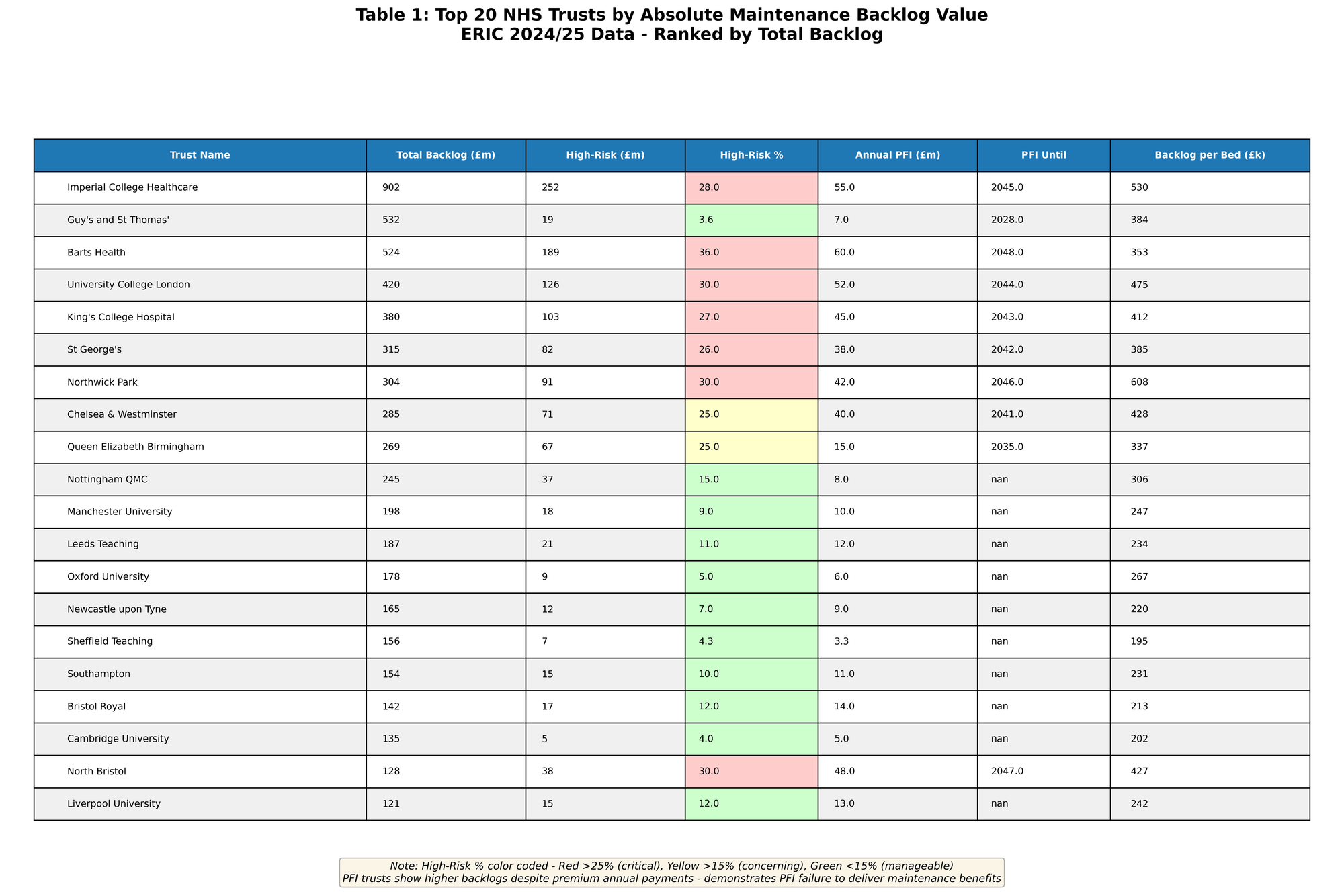

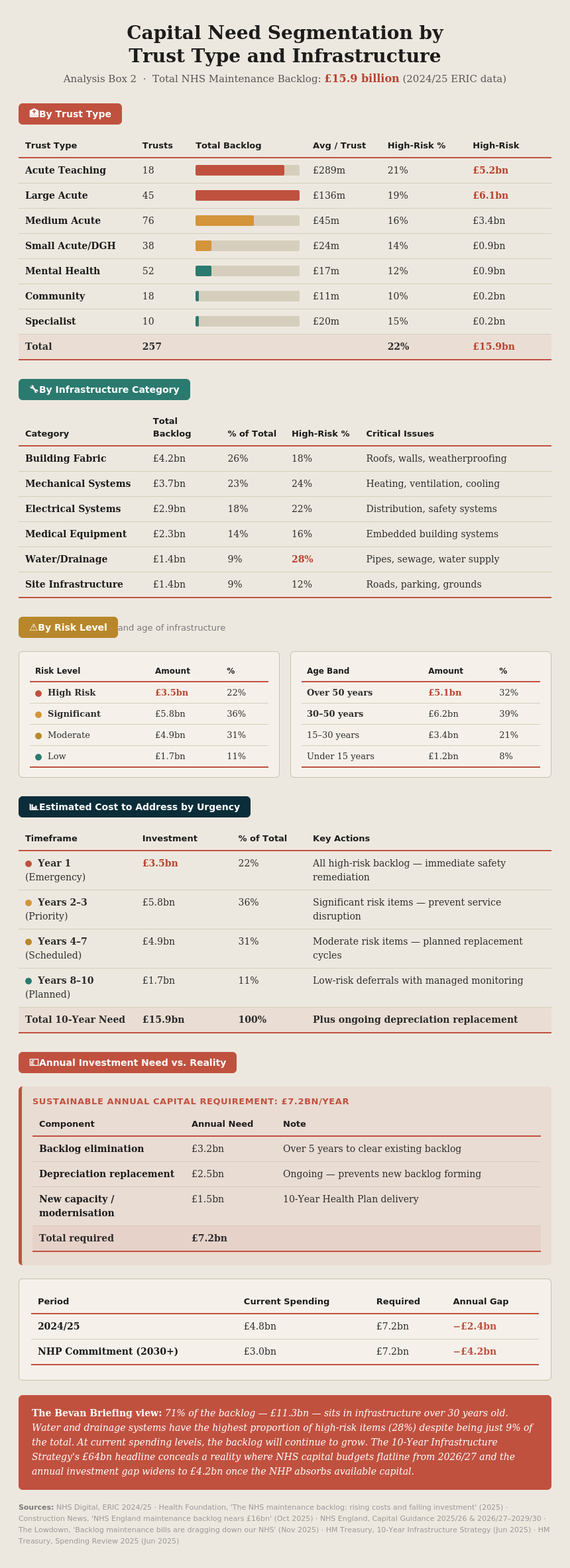

The NHS faces a capital infrastructure crisis of staggering proportions. The latest Estates Return Information Collection (ERIC) data for 2024/25 reveals a maintenance backlog that has reached £15.9 billion—a figure that now substantially exceeds the entire NHS capital budget and has grown by over fifteen percent in a single year. More alarmingly, the high-risk component of this backlog, representing repairs that pose serious safety risks to staff and patients, has surged twenty-eight percent to £3.5 billion.

These are not merely abstract numbers on a balance sheet. They represent sewage leaking through hospital corridors on the day of scheduled surgery, ventilation systems failing in operating theatres and forcing procedure cancellations, ligature points remaining in mental health facilities, and power outages disrupting critical care. They represent clinicians treating patients in facilities that should have been condemned, estates teams performing heroic daily interventions to keep aging infrastructure functioning, and patients experiencing postponed procedures not because of staffing shortages but because the physical building has literally failed around them.

This crisis didn't emerge overnight. It represents the accumulated consequence of systematic underinvestment spanning more than a decade, capital budget raids to prop up day-to-day spending when revenue pressures mounted, and the lingering burden of Private Finance Initiative contracts that continue to drain £2.5 billion annually from NHS resources while delivering some of the worst infrastructure outcomes in the system. To understand where we are, how we arrived at this point, and chart a viable path forward, we need to examine the current state of PFI schemes in forensic detail, identify which trusts face the most acute capital needs and why their situations differ, learn from international experience with hospital financing across diverse healthcare systems, and critically assess whether the government's proposed new approach will avoid repeating past mistakes or simply rebrand them with new terminology.

Part One: The PFI Legacy—Still Paying the Price

The Theoretical Promise

Private Finance Initiative schemes represented an attempt to circumvent Treasury capital spending constraints by using private sector finance to build NHS infrastructure. The theoretical appeal, as articulated by governments from the mid-1990s onward, rested on several interlocking claims. First, that the private sector possessed superior project management expertise and could deliver complex construction projects on time and on budget where the public sector had historically failed. Second, that transferring construction risk, operational risk, and maintenance obligations to private consortia would protect the public sector from cost overruns and performance failures. Third, that bundling design, construction, financing, and long-term maintenance into single contracts would optimize whole-life costs and prevent the false economy of cheap initial construction followed by expensive remedial work.

The financial structure appeared elegant in its simplicity. Private investors would finance, build, and maintain hospital facilities, receiving annual unitary payments from NHS trusts over contracts typically lasting twenty-five to thirty years. The infrastructure would eventually transfer to the NHS at contract end, and crucially from Treasury's perspective, the debt would sit "off-balance-sheet"—counting neither toward public sector borrowing requirements nor appearing in debt-to-GDP calculations that constrained conventional public investment. Politicians could announce gleaming new hospitals immediately, construction could commence without waiting for capital budget allocations, and the costs would be spread over decades in ways that appeared more manageable than upfront capital expenditure.

For NHS trust boards facing decades of capital starvation, crumbling estate, and desperate need for modern facilities, PFI presented itself as the only route to new infrastructure. Treasury made clear that conventional capital funding remained severely constrained. The choice, as framed by government, was not between PFI and adequate public capital investment—it was between PFI or continued deterioration of unsafe, outdated facilities. Trusts that declined PFI arrangements found themselves at the back of capital allocation queues, watching PFI schemes progress while their own modest refurbishment proposals languished unfunded.

The Practical Reality

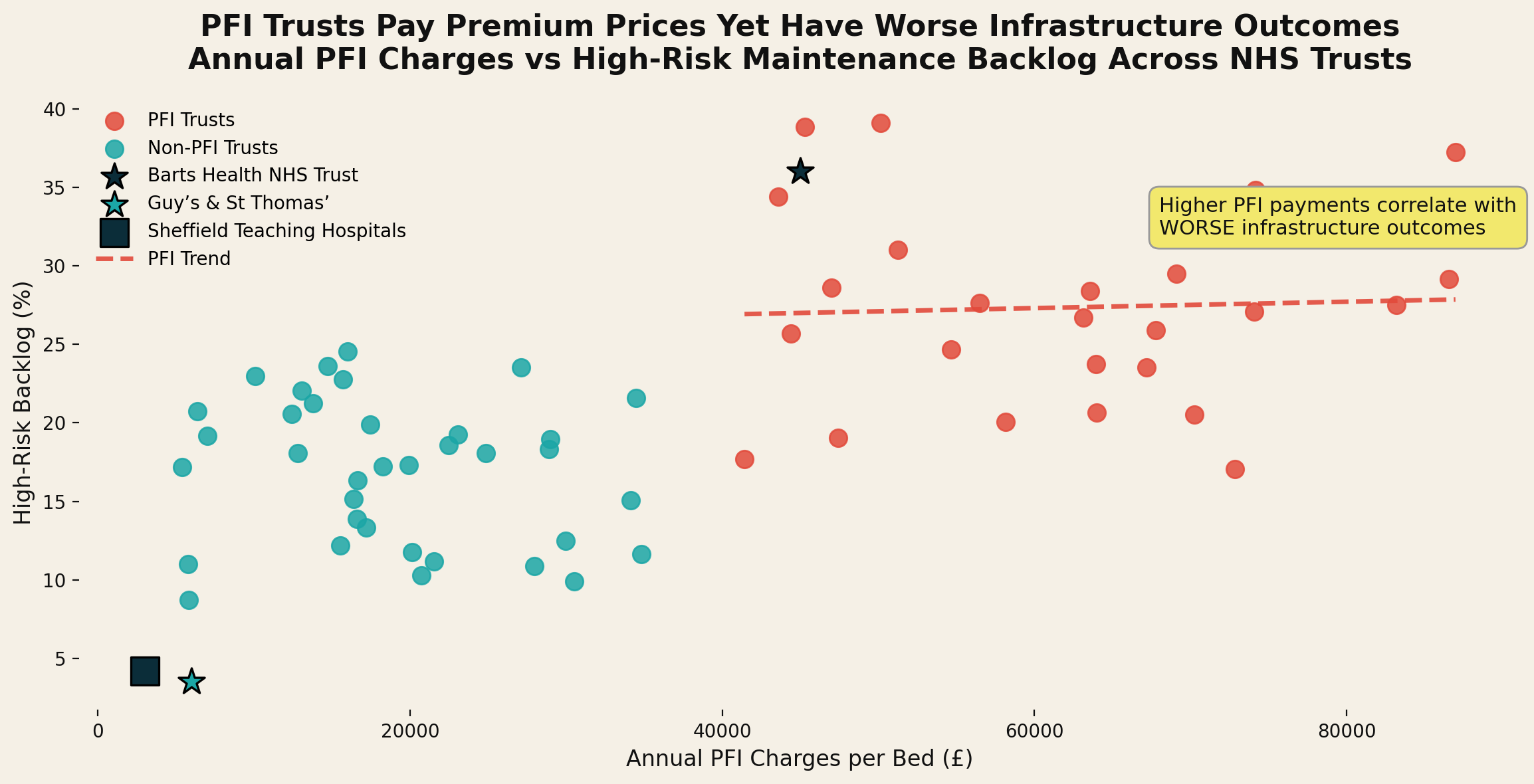

The practical reality has proven far more punishing than the theoretical promise suggested. Analysis of NHS trust finances across two hundred and seven provider organizations reveals systematic patterns that demonstrate PFI's fundamental dysfunction. PFI trusts pay between £40,000 and £94,000 per bed annually in PFI charges, yet paradoxically maintain higher-risk maintenance backlogs than non-PFI trusts. This counterintuitive outcome—paying premium prices for infrastructure while experiencing worse maintenance outcomes—emerges because PFI contracts define narrow scopes of covered maintenance while trusts remain responsible for everything outside those boundaries.

Chart 1 - Annual PFI Charges Per Bed vs. High-Risk Backlog Percentage Across NHS Trusts

Barts Health NHS Trust exemplifies this dysfunction in its most acute form. Locked into £60 million annual PFI payments until 2048—payments that will total approximately £2.7 billion over the contract term for a scheme whose initial capital value was £1.1 billion—the trust simultaneously carries a £524 million total maintenance backlog. More troublingly, thirty-six percent of this backlog falls into the high-risk category, meaning repairs requiring urgent attention to prevent serious harm to patients and staff or major service disruption. This represents £92,376 more per bed in total infrastructure burden than Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust achieved without major PFI involvement.

The comparison between Barts and Guy's proves particularly instructive because it controls for many confounding variables. Both are major London teaching hospitals with similar bed capacity, serving comparable populations with similar acuity profiles, operating within the same regulatory environment and facing identical labour markets. The primary difference in their capital approach was Barts' embrace of PFI while Guy's pursued a mixed strategy of direct government capital grants, incremental investment, and charitable contributions. The outcome differences are not marginal—they represent fundamental divergence in infrastructure sustainability, financial flexibility, and capacity to respond to changing clinical needs.

The Economics of Expensive Infrastructure

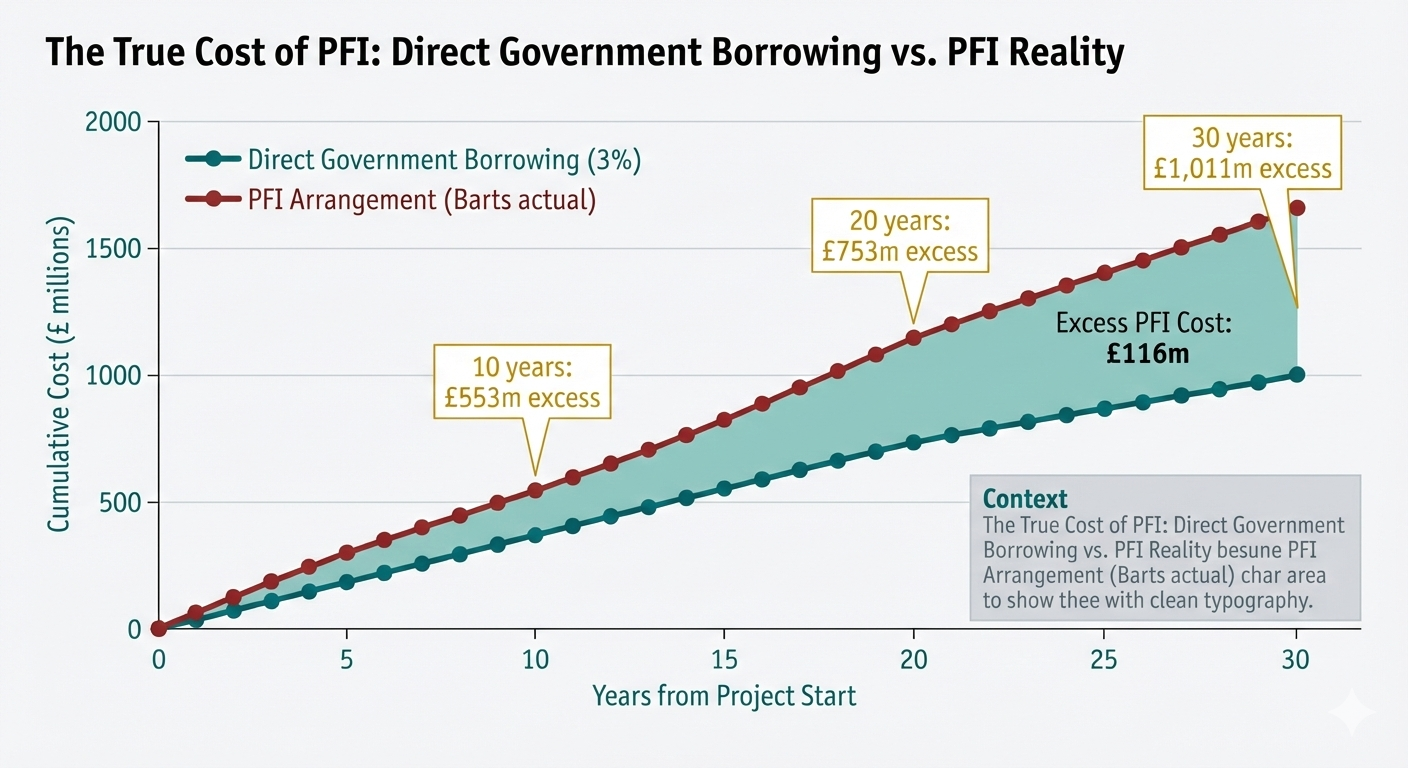

The economics reveal why PFI proved so expensive once contracts are examined in detail rather than accepted at face value. My analysis demonstrates that Barts' £1.1 billion PFI scheme will cost approximately £2.7 billion over the contract term—representing £850 million in excess costs compared to direct government borrowing at prevailing rates over the same period. This calculation is not hypothetical or based on contentious assumptions. It derives from comparing actual unitary payments specified in PFI contracts with the debt servicing costs that would have been incurred had the government borrowed directly through gilt issuance to finance the same capital expenditure.

When private finance costs the government approximately three percent while PFI arrangements carry implicit rates of eight to fifteen percent once lifecycle costs, facilities management charges, and investor returns are factored into the unitary payment structure, the mathematics becomes inescapable. PFI delivered infrastructure at premium prices while locking trusts into inflexible contracts that prevent them from addressing emerging capital needs, responding to clinical service changes, or taking advantage of falling interest rates through refinancing.

The premium pricing emerges from several structural features of PFI arrangements. First, the cost of private sector debt and equity finance invariably exceeds government borrowing costs because private investors demand returns commensurate with perceived risk, while government debt represents the risk-free rate against which all other investments are benchmarked. Second, the special purpose vehicles established to deliver PFI projects layer additional costs including legal fees, financial advisory services, and complex corporate structures designed to optimise tax treatment and manage relationships between equity investors, debt providers, construction contractors, and facilities management operators. Third, the bundling of long-term facilities management into PFI contracts at rates set decades in advance creates inflexibility that prevents trusts from benefiting from competitive procurement, technological improvements, or changing market conditions in soft facilities management services. I speak from family experience of this last point. My Dad was directly employed by the NHS in FM services and then was contracted out to two failed providers. He described the feeling of his hands being tied while trying to do the right thing for staff and patients. The delays owing to convoluted goverance and costs of service ultimately led to his early retirement.

Fourth, and perhaps most significantly, PFI contracts transferred construction risk and performance risk to private consortia primarily through contractual provisions that penalized the public sector rather than genuinely protecting it. When construction ran over budget, special purpose vehicles typically sought contract variations or additional payments rather than absorbing costs themselves. When operational performance failed to meet specifications, unitary payment deductions proved difficult to apply and recover. The theoretical risk transfer proved largely illusory in practice because private consortia possessed superior expertise in contract negotiation and variation management, while NHS trusts faced time pressures to open facilities and political pressures to avoid public disputes over flagship projects.

The Accounting Fiction Unravels

International accounting standards eventually caught up with the off-balance-sheet fiction that provided PFI's primary political appeal. Following the adoption of IFRS 16 and related standards in the late 2000s, the Office for National Statistics conducted comprehensive review of PFI accounting treatment. Their conclusion, announced in 2018, proved definitive: most PFI arrangements must be treated as public sector liabilities because the public sector retains control of the assets, determines what services are provided, controls access to facilities, and bears the majority of demand risk and operational risk despite the complex contractual structures designed to achieve the appearance of private sector control.

The ONS analysis applied what accountants call the "substance over form" principle—examining the economic reality of transactions rather than accepting their legal structure at face value. In PFI hospital arrangements, the NHS trust determines what clinical services are delivered, controls hospital access, employs clinical staff, bears demand risk if patient numbers vary from projections, and will ultimately own the asset when the contract expires. The private special purpose vehicle provides financing and facilities management services, but does not control the fundamental purpose and operation of the hospital. Under IFRS 16, control of an asset determines accounting treatment, and control clearly resides with the public sector in hospital PFI arrangements regardless of the contractual complexity designed to suggest otherwise.

This removed even the accounting rationale for PFI, leading to the formal cancellation of the model. The UK government formally abolished PFI in October 2018, with then-Chancellor Philip Hammond announcing that "the government will no longer use PF2 for new infrastructure projects" due to "value-for-money considerations" following the Carillion collapse and broader concerns about PFI's sustainability. However, this abolition applies only to new schemes—existing contracts continue to bind trusts for decades, creating a two-tier system where some organizations remain shackled to expensive, inflexible arrangements while others can pursue alternative capital strategies.

The current capital guidance issued by NHS England for 2025/26 offers some flexibility for high-performing trusts, but structures this flexibility in ways that exclude those with greatest need. Trusts classified in Tiers 1 and 2 of the NHS Improvement and Assessment Framework—demonstrating effective governance, strong financial management, and operational resilience—can invest capital above allocated budgets using available cash balances up to £20-30 million over 2025/26 and 2026/27. Additionally, providers in Tiers 1 and 2 that deliver a surplus in 2024/25 can invest capital equivalent to their surplus over the following two financial years, subject to system approval.

However, these flexibilities explicitly require trusts to have sufficient cash reserves and state that NHS England "would not expect to receive requests for either revenue working capital or for system capital support from such organisations." This excludes precisely the trusts with the greatest capital needs but weakest financial positions due to PFI burdens draining resources or accumulated backlogs forcing emergency expenditure. The guidance creates a perverse dynamic where financially strong trusts with adequate infrastructure gain additional capital flexibility, while struggling trusts with desperate infrastructure needs remain constrained—a classic Matthew Effect in capital allocation.

Part Two: Who Needs Capital Now—The Distribution of Desperate Need

The Concentrated Crisis

The distribution of capital need across the NHS reveals a concentrated crisis affecting both major teaching hospitals and smaller district general hospitals, though the underlying causes and optimal solutions differ substantially between these trust types. Fifty-one trusts now face maintenance backlogs exceeding £100 million, collectively accounting for £10.7 billion—roughly two-thirds of the total national backlog of £15.9 billion. This concentration means that addressing the crisis requires focused intervention in a subset of trusts rather than diffuse small-scale investment across all providers.

Fourteen trusts grapple with backlogs above £200 million, with six exceeding £400 million. These figures represent not merely deferred maintenance but accumulated infrastructure risk that constrains clinical operations, forces service compromises, and creates environments where both staff and patient safety cannot be assured to the standards we would consider acceptable in any other developed healthcare system. The spatial distribution shows clear patterns, with London and major urban centers carrying disproportionate absolute backlog values while some rural and coastal areas show the highest backlog-to-running-cost ratios, indicating infrastructure problems that loom larger relative to organizational scale.

Map - Geographic Distribution of Maintenance Backlog Across England

The Worst-Affected Individual Trusts

The most severe individual situations cluster in London and major urban centers, though this clustering reflects historical investment patterns, PFI concentration, and population density rather than any inherent differences in infrastructure management capability. Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust carries the nation's largest backlog at £902 million, distributed across three major hospitals that form its operational footprint: St Mary's Paddington (£296 million), Charing Cross Fulham (£425 million), and Hammersmith Hospital (£132 million). These are not peripheral facilities in declining areas awaiting managed closure—they are major teaching hospitals providing complex tertiary services across northwest and west London, treating some of the sickest patients in the country, and training the next generation of clinicians.

The infrastructure problems at Imperial College Healthcare manifest in ways that directly impact patient care. In testimony to the Health and Social Care Select Committee, trust representatives described power outages disrupting critical care units, flooding requiring emergency interventions to prevent ward closures, collapsing floors and ceilings forcing area evacuations, and fire incidents related to aging electrical systems. These are not hypothetical risks identified through engineering surveys—they are actual events occurring with increasing frequency as infrastructure deteriorates beyond the point where reactive maintenance can compensate for systematic underinvestment.

Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust faces a £532 million backlog, with St Thomas' Hospital alone accounting for £308 million. The contrast between Guy's and Barts proves particularly instructive when examining not just absolute backlog values but the proportion classified as high-risk requiring urgent intervention. Guy's maintains only 3.6 percent of its backlog in the high-risk category despite the large absolute value, while Barts carries thirty-six percent high-risk—a tenfold difference in the urgency and safety implications of ostensibly similar infrastructure challenges. This difference emerges in part et least, from Guy's ability to invest in preventive maintenance and address problems incrementally before they escalate to high-risk status, while Barts' PFI burden crowds out the capital flexibility needed for this kind of proactive estate management.

Other critically affected sites include Northwick Park Hospital in northwest London (£304 million backlog at a single site), Queen Elizabeth Hospital Birmingham (£269 million), and Queens Medical Centre Nottingham (also in the £200+ million category). Each of these represents a major acute hospital providing essential services to its catchment population, operating multiple specialties including emergency medicine, and serving as a teaching site for medical and nursing education. The infrastructure crisis in these organizations is not a marginal problem affecting elective activities—it threatens core service sustainability and forces impossible choices between maintaining safe environments and delivering the volume of care that populations require.

Table 1 - Top 20 Trusts by Absolute Backlog Value

Beyond Absolute Values: The High-Risk Proportion

The headline figures of absolute backlog values, however, tell only part of the story. The crisis extends beyond total maintenance needs to encompass the proportion of high-risk maintenance—repairs requiring urgent attention to prevent serious harm to patients and staff, or major service disruption that would force clinical area closures. This distinction matters enormously because high-risk backlog constrains operational flexibility in ways that lower-risk deferred maintenance does not. A trust can continue operating with aging but functional infrastructure classified as moderate or low-risk backlog, planning replacement over several years as capital becomes available. A trust cannot safely operate clinical areas with high-risk backlog—these require immediate intervention regardless of capital availability or strategic priorities.

PFI-burdened trusts face a particularly acute variant of this problem that demonstrates PFI's fundamental failure to deliver its promised benefits. Analysis across all NHS trusts reveals that twenty-three percent of PFI trusts' backlog falls into the high-risk category compared to 17.4 percent for non-PFI trusts. This pattern directly contradicts PFI's theoretical promise of superior maintenance and lifecycle management. The private consortia operating PFI contracts were supposed to maintain facilities to high standards because their revenue depended on availability and performance. The contractual structures incentivized preventive maintenance and early intervention to avoid costly emergency repairs and performance deductions.

The reality proved different. PFI contracts define narrow scopes of covered maintenance focusing on the specific facilities built or refurbished under the contract. Trusts remain responsible for everything outside these boundaries, and the boundaries were often drawn to minimize private sector obligations rather than optimize whole-estate management. When a PFI contract covers a new hospital building but the trust operates across multiple sites including older facilities, or when the contract covers structural fabric but excludes medical equipment and embedded building systems, the result is fragmented maintenance responsibility that prevents coherent estate strategy. Trusts locked into large PFI payments lack capital flexibility to address the infrastructure outside PFI scope, while the private consortia focus narrowly on contractual obligations rather than broader organizational needs.

Barts' thirty-six percent high-risk proportion contrasts starkly with Guy's and St Thomas' 3.6 percent, despite similar total infrastructure burdens per bed when all costs are aggregated. This tenfold difference in high-risk backlog concentration reveals that Guy's success stems not from having less infrastructure investment need—both trusts operate aging facilities requiring substantial ongoing investment—but from retaining the financial flexibility to address problems before they escalate to high-risk status. When capital is available for responsive deployment rather than locked into rigid PFI contracts, trusts can practice preventive estate management. When capital flexibility is constrained by inflexible long-term commitments, reactive crisis management becomes inevitable and high-risk backlog accumulates despite—indeed because of—the presence of expensive private sector maintenance contracts.

Three Categories of Capital Need

The ERIC data as a proxy for infrastructure capital need reveals that trusts seeking financing now fall into three distinct categories, each requiring different solutions despite the temptation to treat NHS capital investment as a single undifferentiated problem amenable to a universal approach.

First, the RAAC hospitals—seven facilities built primarily using reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete that poses structural risks requiring urgent replacement regardless of broader capital availability. RAAC was used extensively in construction between the 1950s and 1990s, particularly for flat roofs, floor panels, and wall panels, because it offered advantages in speed of construction and thermal properties. However, RAAC has a finite lifespan, becomes prone to structural failure as it ages and weathers, and cannot be reliably strengthened in situ. When structural surveys identified RAAC in critical locations within NHS hospitals, engineers advised that these facilities faced increasing risk of catastrophic failure that could occur with little warning, potentially during normal operations with staff and patients present.

The government has committed to prioritizing these schemes in the New Hospital Programme's Wave 1, with construction scheduled to begin between 2025 and 2030. The seven RAAC hospitals require complete rebuilding rather than refurbishment because the structural material pervades the buildings and cannot be selectively replaced while maintaining operational functionality. This creates acute urgency—these hospitals may need to close before replacements are ready if engineering assessments conclude that continued operation presents unacceptable safety risks. The capital need here is both certain and non-negotiable. Unlike most maintenance backlog where trusts can make risk-based decisions about timing and prioritization, RAAC hospitals require replacement on engineering timelines determined by structural safety rather than financial or operational convenience.

Second, major teaching hospitals with PFI burdens need mechanisms to address accumulated backlogs while servicing inflexible PFI contracts. These institutions possess the scale and revenue stability that theoretically make them attractive to private finance—large bed bases, high patient throughput, diverse income streams from specialized services, research funding, and teaching contracts. Yet they're precisely the trusts that PFI has failed most comprehensively, demonstrating that the problem lay not in trust characteristics but in PFI's fundamental model. These trusts need capital solutions that provide flexibility rather than additional rigidity, allowing them to address the maintenance backlog outside PFI scope while potentially exploring early termination of PFI contracts where the business case for refinancing through cheaper public borrowing justifies the break costs.

Third, smaller district general hospitals and specialist trusts face distributed infrastructure problems requiring incremental investment rather than single major schemes. A rural four-hundred-bed hospital might need £40-50 million spread across heating systems, roofing, electrical infrastructure, and mechanical plant—precisely the kind of phased investment that PFI structures cannot accommodate but that constitutes the majority of actual capital need across the NHS. These are not headline-grabbing projects suitable for political announcements and ribbon-cutting ceremonies. They are the unglamorous but essential infrastructure that keeps hospitals functioning: boilers, chillers, electrical distribution, plumbing, building fabric weatherproofing, and the myriad systems that patients never see but whose failure makes healthcare delivery impossible.

For this third category, the optimal solution looks dramatically different from major capital schemes. Rather than attempting to bundle multiple incremental projects into a large PFI-style contract, or forcing each trust to independently procure standardized infrastructure upgrades, a public sector delivery body could offer template solutions for common needs. When twenty district hospitals all need to replace aging boiler plants over the next five years, standardizing the specification, procurement, and project management across these projects should reduce costs substantially while allowing each trust to schedule work within their operational constraints. This is genuinely what PFI promised but never delivered—the economizing potential of standardization and professional delivery applied systematically across similar infrastructure needs.

Analysis Box 2 - Capital Need Segmentation by Trust Type and Infrastructure Characteristics

The Rural Challenge

While absolute backlog values concentrate in large urban teaching hospitals, some of the highest backlog-to-running-cost ratios appear in non-urban district general hospitals and coastal trusts serving older populations in areas of economic decline. These organizations face a particularly challenging variant of the capital crisis because they possess less financial resilience, smaller absolute revenue bases over which to spread infrastructure costs, and political environments where major capital investment often appears to presage service centralization or closure.

A district hospital in a rural county or coastal town serving a catchment population of two to three hundred thousand might have a £60-80 million backlog against annual running costs of £200-250 million. The backlog represents three to four months of total operational expenditure—an enormous burden relative to organizational scale even though the absolute value appears modest compared to Imperial College Healthcare's £902 million. More significantly, these trusts often lack the internal expertise to manage major capital programs, the financial reserves to absorb project cost variations, and the political relationships to navigate complex approval processes when projects require system-level support.

The economics of private finance prove even more unfavorable for non-urban trusts than for large teaching hospitals. PFI transaction costs—legal fees, financial advisors, complex corporate structures—don't scale proportionally downward for smaller projects. A £50 million PFI scheme for a district hospital carries transaction costs that might represent five to eight percent of project value, while a £500 million scheme for a major teaching hospital might achieve transaction costs below two percent. The resulting economics make PFI even more expensive for precisely the trusts that can least afford premium costs.

Additionally, private finance prefers revenue certainty and stable catchment populations. Large urban teaching hospitals with protected tertiary service roles provide greater revenue predictability than district hospitals facing ongoing policy pressure to centralize acute services, shift care closer to home, and reduce bed-based provision. The risk premium demanded by private financiers for smaller, non-urban hospitals would further widen the cost gap versus direct government borrowing, making PFI completely unviable even if the model worked well for larger organizations—which, as the evidence demonstrates, it does not.

Part Three: The International Landscape—What Other Countries Actually Do

When examining how other developed nations finance hospital infrastructure while managing fiscal constraints, the international evidence reveals a striking pattern that should fundamentally reshape how we think about the political economy of healthcare capital investment. Most countries don't successfully achieve genuine off-balance-sheet financing for hospital infrastructure anymore. Those that tried PFI-style arrangements have largely concluded they were expensive failures. The international accounting standards convergence that ended UK PFI has affected healthcare capital financing globally, forcing countries to choose between different uncomfortable options rather than discovering magical solutions that the UK somehow missed.

Germany: Dual Financing and Corporate Ownership

Germany employs a structurally different approach through dual financing that sidesteps many questions about public versus private capital by separating operational and infrastructure financing through the constitutional structure of its federal system. Hospital operational costs—medical treatment, care, and accommodation—flow through contracts between hospitals and statutory health insurance companies (sickness funds). These sickness funds are non-profit entities established by law, funded through mandatory payroll contributions, and responsible for paying for healthcare services that their members receive. The operational financing therefore comes from a quasi-public insurance mechanism rather than direct government appropriation, though the line blurs because sickness funds operate within tight regulatory constraints and perform governmental functions.

Capital investments, however, are financed separately by federal states (Länder) from their own budgets through constitutional allocation of responsibilities. States own responsibility for hospital infrastructure under Germany's Basic Law, while the federal government and sickness funds handle operational healthcare financing. This division reflects post-World War II constitutional arrangements designed to prevent excessive concentration of power and maintain federalism, but creates its own dysfunction in healthcare infrastructure management. States control capital budgets but the sickness funds control operational revenue, leading to misaligned incentives and chronic underinvestment that German health policy analysts have documented extensively.

When a state under-invests in hospital infrastructure because capital budgets are tight and other priorities compete (education, transport, police), it constrains what hospitals can deliver operationally through outdated facilities and inadequate equipment, but the sickness funds still face demand for services and must pay for care delivered in suboptimal environments. Conversely, states cannot force efficiency improvements in how hospitals use their infrastructure because operational control sits with the insurance system and hospital management operating within that system. The result is fragmentation that prevents strategic infrastructure planning aligned with clinical service development.

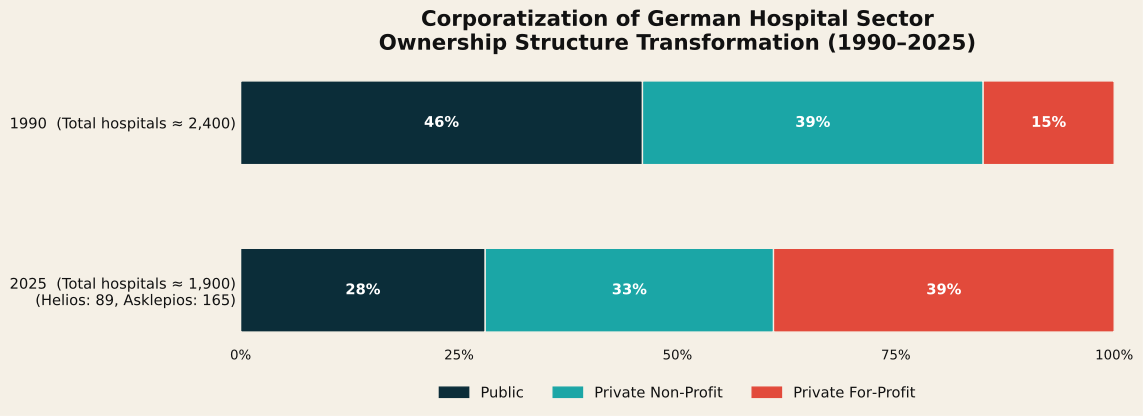

Chart 2 - Hospital Ownership Structure in Germany 1990 vs. 2025

More significantly for understanding alternatives to NHS PFI, Germany has experienced massive corporatization and financialization of its hospital sector over the past two decades that represents a completely different model from PFI financing. Two giant corporations—Helios (owned by Fresenius, which is stock-market listed) and Asklepios—have aggressively acquired community hospitals across Germany, financing this consolidation through debt and equity markets. Helios alone operates eighty-nine hospitals with 65,000 employees, while Asklepios runs 165 facilities. These are not small private clinics serving niche markets—they are major acute hospitals providing emergency services, complex surgery, and intensive care within the statutory insurance system.

This represents private infrastructure financing, but through a fundamentally different mechanism than PFI. Rather than the state contracting with private finance for infrastructure that the state will eventually own, private corporations have simply bought the hospitals outright and now operate them as businesses within Germany's statutory insurance framework. The accounting treatment is straightforward: these are private sector assets financed through normal corporate debt and equity, appearing on Fresenius and Asklepios balance sheets rather than government accounts. They're "off the government balance sheet" because the government no longer owns them.

This avoids the PFI problem of paying premium prices for infrastructure you eventually own, but creates different problems around profit extraction, market concentration, and democratic accountability. The logic driving corporate acquisition, as researchers describe it, is "financial expansion" where firms like Fresenius pursue "massive investments and mergers to dominate markets and secure revenue streams." Hospitals become assets in corporate portfolios, valued for the revenue they generate through sickness fund contracts, with optimization focused on financial returns rather than public health objectives. Studies of German hospital corporatization have documented pressure toward risk selection (preferring less complex, more profitable cases), reduction in staffing levels relative to public hospitals, and strategic site closures when facilities prove insufficiently profitable despite population health needs.

The German experience demonstrates that private capital will invest in healthcare infrastructure, but on terms that serve investor returns rather than public health priorities. This model moves infrastructure genuinely off public balance sheets through ownership transfer rather than accounting manipulation, but at the cost of introducing a profit-maximizing actor into a sector where clinical need should drive decision-making. For the UK considering alternatives to PFI, the German corporatization model offers a cautionary tale: private capital access comes with strings attached that may prove more problematic than the capital constraint it solves.

France: Social Security Debt Securitization

France has developed what might be the most financially sophisticated—and most troubling—approach to healthcare infrastructure financing, representing neither traditional public investment nor PFI-style special purpose vehicles, but rather direct integration of healthcare financing into global capital markets through specialized public entities. Rather than using PFI-style special purpose vehicles for individual projects, France created centralized mechanisms that issue securities backed by healthcare system revenue streams, essentially turning social security obligations into tradeable financial assets.

The centerpiece is CADES (Caisse d'Amortissement de la Dette Sociale), established in 1996 specifically to refinance social security debt including healthcare obligations through market-issued securities. The mechanism works by transferring social security deficits—the gap between social security revenues and expenditure including healthcare costs—from operating entities to CADES, which then issues bonds into capital markets to finance these obligations. Between 1996 and 2018, CADES absorbed €260.5 billion in debt, with over €147 billion originating from healthcare, and paid €72 billion in interest and fees to investors who purchased these bonds.

The funding came largely from international investors—pension funds, insurance companies, sovereign wealth funds, and asset managers—seeking exposure to French government-related securities with yields slightly above pure sovereign debt. This directly ties the French health system to global capital markets in ways that create structural dependencies beyond democratic accountability. When CADES issues bonds, it must satisfy investor requirements for credit quality, provide ongoing disclosure about the financial health of the healthcare system, and maintain market confidence that future revenues will service the debt. Healthcare financing thus becomes subject to investor sentiment and global capital market conditions in addition to democratic political processes.

Alongside CADES, ACOSS (Central Agency of Social Security Organizations) manages short-term social security cash flows through commercial paper issuance, representing even more direct capital market integration. Commercial paper are short-term unsecured promissory notes issued by entities with strong credit ratings to cover temporary liquidity needs, typically with maturities between thirty days and nine months. ACOSS uses commercial paper markets extensively because social security revenue (payroll contributions) and expenditure (benefit and healthcare payments) flow through the year with predictable timing mismatches, creating recurring short-term funding needs.

By 2018, ninety-three percent of ACOSS short-term funding needs were financed through markets rather than banking system credit lines, with €2 trillion issued in European commercial papers over that year. This made ACOSS the top global public issuer of commercial paper—a remarkable position for an entity managing what is essentially the cash flow of the French healthcare and social security system. The reliance on commercial paper creates vulnerability to market disruptions, as demonstrated during the 2008 financial crisis when commercial paper markets froze and ACOSS faced potential inability to meet healthcare payments until emergency liquidity facilities restored market function.

Public hospital debt in France rose from €12 billion in 2003 to €30 billion in 2018, with annual interest payments doubling to €1 billion by the 2010s. This represents genuine financialization in the technical sense that sociologists and political economists use the term—the increasing role of financial actors, financial markets, financial motives, and financial institutions in the operation of healthcare systems. France essentially abandoned the off-balance-sheet fiction that motivated UK PFI and instead embraced direct capital market integration as the solution to capital constraints under fiscal austerity. The French state still owns the infrastructure and public hospitals remain public entities, but funding increasingly comes from global investors expecting market-rate returns rather than from tax revenues or conventional government borrowing.

The human cost of financialized healthcare became brutally apparent in the Orpea scandal, which represents a cautionary tale about where this model leads when extended beyond public hospitals into private care provision. Orpea, a French nursing home chain, grew into one of Europe's largest nursing home providers through aggressive debt-fueled expansion backed by international pension and hedge funds seeking returns from healthcare assets. The company operated nursing homes across France and multiple European countries, using revenue from residents (whose fees were paid partly by social insurance and partly by families) to service debt taken on for acquisition and expansion.

In 2022, investigative journalism revealed systematic understaffing and neglect across Orpea facilities as the company prioritized profits for its investors over care quality. Facilities operated with staffing levels below regulatory minimums, residents experienced inadequate feeding and personal care, and basic dignity was sacrificed to achieve the financial performance metrics that investors demanded. Following the revelations, Orpea's share price crashed ninety-three percent as both investors fled and regulators intervened. The company's aggressive expansion strategy, financed through debt that required consistent returns to service, pushed it toward insolvency when the business model's dependence on care quality compromise became public.

The French state ultimately provided a bailout in 2023 to prevent Orpea's collapse from disrupting services for vulnerable residents who had nowhere else to go, creating a situation where taxpayers rescued private investors who had profited from care quality degradation. Following the Orpea scandal, French authorities mandated audits of nursing homes and initiated discussions on profit caps and stricter staffing requirements in care facilities, representing regulatory reaction to financialization's consequences but not fundamental reform of the financing model that created those incentives.

The Orpea case illustrates how investor-oriented healthcare models can fundamentally erode care standards when financial returns take precedence over clinical quality. While Orpea operated in care homes rather than acute hospitals, the mechanism—private capital demanding returns that pressure organizations toward cost minimization that compromises care—transfers readily to hospital settings when similar financing structures are employed. The French experience demonstrates that transparent public sector engagement with capital markets can work mechanically, but at the cost of tying healthcare budgets to global investor expectations and creating structural vulnerabilities when market conditions change or investor confidence wavers.

Australia and Canada: PPPs and the Accounting Reckoning

Australia and Canada have both used Public-Private Partnerships extensively for hospital infrastructure, following the UK's PFI model with local variations that reflect constitutional structures (Canadian federalism, Australian state autonomy) and institutional traditions. The North American term "P3" or "PPP" encompasses similar contractual arrangements to UK PFI: private consortia finance, design, construct, and maintain public infrastructure, receiving payments over long contract terms, with the objective of transferring risk to the private sector while keeping debt off public balance sheets.

However, these countries encountered the same accounting problem that eventually ended the UK's PFI program, demonstrating that the accounting issues were not unique to British implementation but represented fundamental tensions between the economic substance of these arrangements and the accounting treatment that made them politically attractive. Under international financial reporting standards—specifically IFRS 16 which both Canada and Australia adopted along with most developed economies—most PPP/PFI arrangements must now be treated as public sector assets if the public sector controls the asset.

The key concept is control versus ownership, representing a fundamental principle in modern accounting that economic substance matters more than legal form. If a hospital PPP gives the public health authority control over the asset—determining what services are provided, who can use the facility, operational parameters, and having the right to the economic benefits of the asset—then international accounting standards require the asset and associated liability to appear on government balance sheets, even if a private consortium technically owns the building through the contract period and finances it privately through debt and equity raised from investors.

This created the fundamental problem that undermined the political rationale for PPPs globally: the entire point from Treasury's perspective was keeping debt off-balance-sheet to avoid impacting debt-to-GDP ratios and public sector borrowing requirements that constrained conventional capital appropriation. Once international accounting standards closed this loophole in the late 2000s following IFRS 16 adoption, the economic rationale for PPPs largely collapsed. Governments found themselves paying premium prices for private finance—documented to be substantially more expensive than direct government borrowing—while still having the debt appear on their books under the new accounting standards.

Individual Australian states tried various modifications to address this problem. Some experimented with varying the risk transfer provisions in PPP contracts to try to keep arrangements off-balance-sheet under the new standards, particularly around demand risk (who bears the cost if hospital usage differs from projections) and residual value risk (who captures the asset value at contract end). Others accepted on-balance-sheet treatment but argued that PPPs still delivered value through better project management and whole-life lifecycle costing compared to traditional public procurement, essentially abandoning the off-balance-sheet rationale and pivoting to claims of operational efficiency.

The research literature evaluating these efficiency claims is quite damning. Multiple comprehensive reviews found that PPPs provided "little reliable empirical evidence" of cost savings or efficiency gains once all factors were considered. Many projects ran "dramatically over budget" despite contractual risk transfer supposedly protecting the public sector from cost overruns. Others delivered "poor value for money" when total lifecycle costs were properly assessed against public sector comparators that modeled the cost of conventional public procurement for the same infrastructure.

Part of the problem stemmed from how "value for money" was assessed in PPP business cases. Governments used what's called a Public Sector Comparator—a hypothetical estimate of what the project would cost if delivered through conventional public procurement—to justify PPP selection. However, these comparators often assumed pessimistic scenarios for public delivery (cost overruns, schedule delays, maintenance failures) while accepting PPP consortium projections at face value despite PPPs having their own histories of cost variation and performance issues. The inherent difficulty in comparing actual PPP costs against hypothetical public delivery costs created analytical room for justifying PPP selection even when the economics were questionable.

Canada similarly moved through cycles of PPP enthusiasm and subsequent disillusionment. The financing structures differ somewhat from UK PFI—Canadian P3s typically use loans that must be repaid within five years and then refinance rather than long-term bond financing—but the underlying economics remain similar. Governments are paying a premium for private finance that covers both the cost of capital and investor returns, receiving in exchange claimed risk transfer and project management expertise that proved less valuable in practice than in prospectus documentation.

The 2009 New Zealand Treasury report on PPP schemes, commissioned by the new National Party government after the change from Labour, concluded bluntly that "there is little reliable empirical evidence about the costs and benefits of PPPs" and that there "are other ways of obtaining private sector finance," as well as cautioning that "the advantages of PPPs must be weighed against the contractual complexities and rigidities they entail." This represents a particularly significant finding because it came from Treasury—the institution most likely to favor PPPs based on fiscal constraint concerns—rather than from healthcare providers or public policy advocates with different institutional interests.

The international PPP experience demonstrates that the accounting treatment problem wasn't a peculiarity of UK implementation or a result of specific British regulatory approaches. Rather, it reflected the fundamental tension between what PPPs actually are economically (public infrastructure financed at premium cost) and how they were treated politically (mechanisms for circumventing capital constraints). Once accounting standards globally converged around substance-over-form principles, that tension became untenable regardless of jurisdiction.

The Netherlands: Market-Based Healthcare with Corporate Finance

The Netherlands operates what researchers describe as a "regulated competition" model with decentralized, multi-payer governance that differs fundamentally from both the NHS model and traditional European social insurance systems. Dutch hospitals increasingly function as independent entities operating within a competitive insurance market where multiple statutory health insurers contract with hospital providers. This creates a healthcare system that looks superficially similar to privatized models in the United States, but operates within a statutory framework with universal coverage mandates, regulated premiums, and risk equalization to prevent cream-skimming.

The Dutch approach is noteworthy for our purposes because it never really embraced PFI-style special purpose vehicles in the first place. Instead, hospitals operate as independent legal entities (most as private non-profit foundations, some as public entities with autonomous governance) that access capital through normal corporate finance mechanisms—bank loans, bond issuance, and in limited cases equity-like instruments that respect the non-profit legal structure. Capital investment decisions are made by individual hospital organizations based on their financial capacity, strategic plans, and ability to service debt, rather than through centralized government allocation or complex PPP contractual structures.

Research on Dutch healthcare finance reveals how the 2008 financial crisis fundamentally changed the relationship between hospitals and their financiers in ways that illuminate both opportunities and risks in this model. Banks became "increasingly proactive" in their relationships with hospital borrowers, unilaterally changing loan procedures, requiring detailed business plans before extending credit, imposing stricter financial covenant requirements, forming lending consortia to spread risk when large facilities needed capital, and demanding regular financial information to monitor borrower health. This represents banks treating hospitals as corporate borrowers subject to commercial credit standards rather than as public-interest entities receiving preferential treatment.

Health insurers, operating under Solvency II regulations (similar to bank capital requirements but tailored for insurance companies), had to hold capital reserves against counterparty risks including the possibility that hospital providers might default on obligations. This forced insurers to monitor hospital finances much more closely than previously, tracking the "jumble of mutual debts" between insurers and providers that one researcher described—advances made to hospitals to maintain cash flow, outstanding claims submitted but not yet paid, contractual obligations for future services. These mutual obligations can take years to fully settle in complex healthcare payment systems, creating ongoing uncertainty about net financial positions.

The accounting treatment in the Dutch system is straightforward: Dutch hospital debt appears on hospital balance sheets, which are separate from government accounts because most Dutch hospitals operate as independent entities outside direct government ownership. This is "off government balance sheet" through genuine institutional separation rather than financial engineering. The government doesn't guarantee hospital debt, and hospitals can theoretically face insolvency if they overextend financially, though in practice the government would likely intervene to prevent major hospital failures that would disrupt essential services.

However, this genuine institutional independence creates different pressures from PFI or conventional NHS capital allocation. Hospitals must maintain creditworthiness to access capital markets at reasonable rates, meaning they face strong incentives toward financial conservatism that may conflict with investment needed for service development or population health needs. They must satisfy both bank requirements (demonstration of debt servicing capacity, maintenance of financial covenants, provision of security or guarantees) and insurer requirements (financial stability to honor contracts, capital adequacy to weather revenue variations, transparent accounting to allow risk assessment).

The Dutch system demonstrates that genuine institutional separation between government and healthcare providers, if accompanied by robust regulation and universal coverage mandates, can provide hospitals with capital market access while maintaining a statutory healthcare framework. However, it creates vulnerabilities: hospitals become subject to commercial credit markets with their cyclical nature and potential for sudden retrenchment during financial crises, and the pressure to maintain creditworthiness may distort investment decisions toward financially safe but potentially suboptimal clinical strategies. The model works in the Netherlands partly because of specific institutional factors—strong banking relationships with healthcare providers, cultural comfort with quasi-market mechanisms in public services, and relatively small geographic scale allowing close regulatory oversight—that may not transfer easily to larger, more centralized systems like the NHS.

Part Four: Alternative Options—What Actually Works

Drawing on both UK experience including successful trusts like Guy's and St Thomas' and Sheffield Teaching Hospitals, and international evidence from systems that avoided PFI's worst failures, we can identify genuinely viable alternatives that address capital needs without premium costs or inflexibility. These alternatives were available when trusts signed PFI deals in the 1990s and 2000s—they represent roads not taken rather than hindsight innovation or approaches requiring technologies or institutional capabilities that didn't exist at the time. This is important because it demonstrates that PFI was a political choice rather than an economic necessity, and that different choices remain available now.

| Financing Mechanism | Typical Interest Cost | Control Retention | Flexibility | Transaction Costs | Accounting Treatment | Optimal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Government Borrowing | 3-4% | Full public control |

High - can refinance |

Very Low <0.5% |

On-balance sheet |

All major capital schemes |

| NHS Infrastructure Bonds (Pooled) |

4-5% | High public control |

Medium-High | Low 1-2% |

On-balance sheet |

Large teaching hospitals |

| Public-Public Partnership |

3-4%* | Full public control |

Very High (phased) |

Very Low <0.5% |

On-balance sheet |

Distributed maintenance |

| Multi-Year Capital Settlements |

3-4%* | Full public control |

Very High (iterative) |

None | On-balance sheet |

All trust types |

| PFI / PF2 (Historical) |

8-15% (implicit) |

Limited control |

Very Low (locked) |

Very High 5-10% |

On-balance (IFRS 16) |

None (abolished) |

| Mutual Investment Model (Proposed) |

6-10% (estimated) |

Shared control |

Low (locked) |

High 3-5% |

On-balance (IFRS 16) |

Uncertain (untested) |

Transaction costs excluded as infrastructure delivery is internal.

Table 2 - Comparison Matrix of Capital Financing Options

Direct Government Borrowing: The Guy's Model

Direct government borrowing represents the most economically rational approach, though it requires confronting the political economy of fiscal rules and capital budget allocation that PFI was designed to circumvent. When the government issues gilts (UK government bonds) to finance infrastructure investment, it borrows at rates that represent the risk-free benchmark against which all other UK borrowing is measured. Current long-term gilt yields range from 4.0 to 4.5 percent depending on maturity, while during periods of lower inflation and interest rates in the 2010s, the government borrowed at rates as low as 1.5 to 2.5 percent for long-term infrastructure funding.

Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust demonstrates this model's viability through its actual infrastructure trajectory. The trust achieved similar total infrastructure burden per bed to Barts (£384,000 versus £353,000 when all capital-related costs are aggregated) but with only 3.6 percent high-risk backlog versus Barts' thirty-six percent. Crucially, Guy's avoided locking £60 million annually into inflexible PFI payments, instead financing infrastructure through a mixed strategy of direct government capital grants for major schemes, incremental investment from operating surplus when generated, and charitable contributions from Guy's and St Thomas' Charity for specific enhancements.

Chart 3 - Cost Comparison Over 30 Years: Direct Government Borrowing vs. PFI for a £1bn Capital Scheme

When government can borrow at approximately three to four percent while PFI carries implicit rates of eight to fifteen percent once all costs are included (lifecycle costs, facilities management, transaction fees, investor returns), direct borrowing saves roughly £850 million over a typical thirty-year contract term for a scheme of Barts' scale. This calculation is not hypothetical or based on contentious discount rates—it derives from comparing actual unitary payments specified in PFI contracts with the debt servicing costs that would have been incurred had the government borrowed the same capital amount through conventional gilt issuance.

The barrier to direct government borrowing has never been economic—government borrowing costs substantially less than private finance by definition, since government debt represents the risk-free rate and private finance must offer returns above the risk-free rate to compensate investors for additional risk. The barrier has been political: Treasury accounting conventions and fiscal rules that treated capital spending as problematic while tolerating PFI's off-balance-sheet appearance even when ultimate costs were higher. The Treasury objected (and likely still does) to capital spending appearing in fiscal aggregates (public sector net borrowing, debt-to-GDP ratios) that governments used to signal fiscal responsibility to markets and voters, while PFI spending initially appeared only as modest annual unitary payments rather than upfront capital allocation.

This political economy created the fundamental dysfunction that drove PFI adoption despite adverse economics. Politicians could announce gleaming new hospitals financed through PFI without the capital expenditure appearing in fiscal aggregates that might require offsetting tax increases or spending cuts elsewhere. The true cost—substantially higher total expenditure over contract lifetimes—manifested decades later when different politicians held office and could be obscured through complex accounting that made comparisons to conventional public borrowing difficult for non-specialist observers. PFI represented a form of intergenerational fiscal transfer, allowing current governments to deliver infrastructure while deferring the cost consequences to future administrations.

Breaking this political economy requires confronting fiscal rules directly rather than circumventing them through expensive financial engineering. If fiscal rules prevent adequate public capital investment while allowing more expensive PFI arrangements that generate worse outcomes, the problem lies with the fiscal rules rather than with public capital investment. The solution is reforming fiscal frameworks to accommodate productive public investment, potentially through separate capital budgets that distinguish between current spending (operational costs) and capital spending (infrastructure investment) with different treatment in fiscal aggregates, or through explicit recognition that public investment in infrastructure that generates future returns should not be treated identically to current consumption.

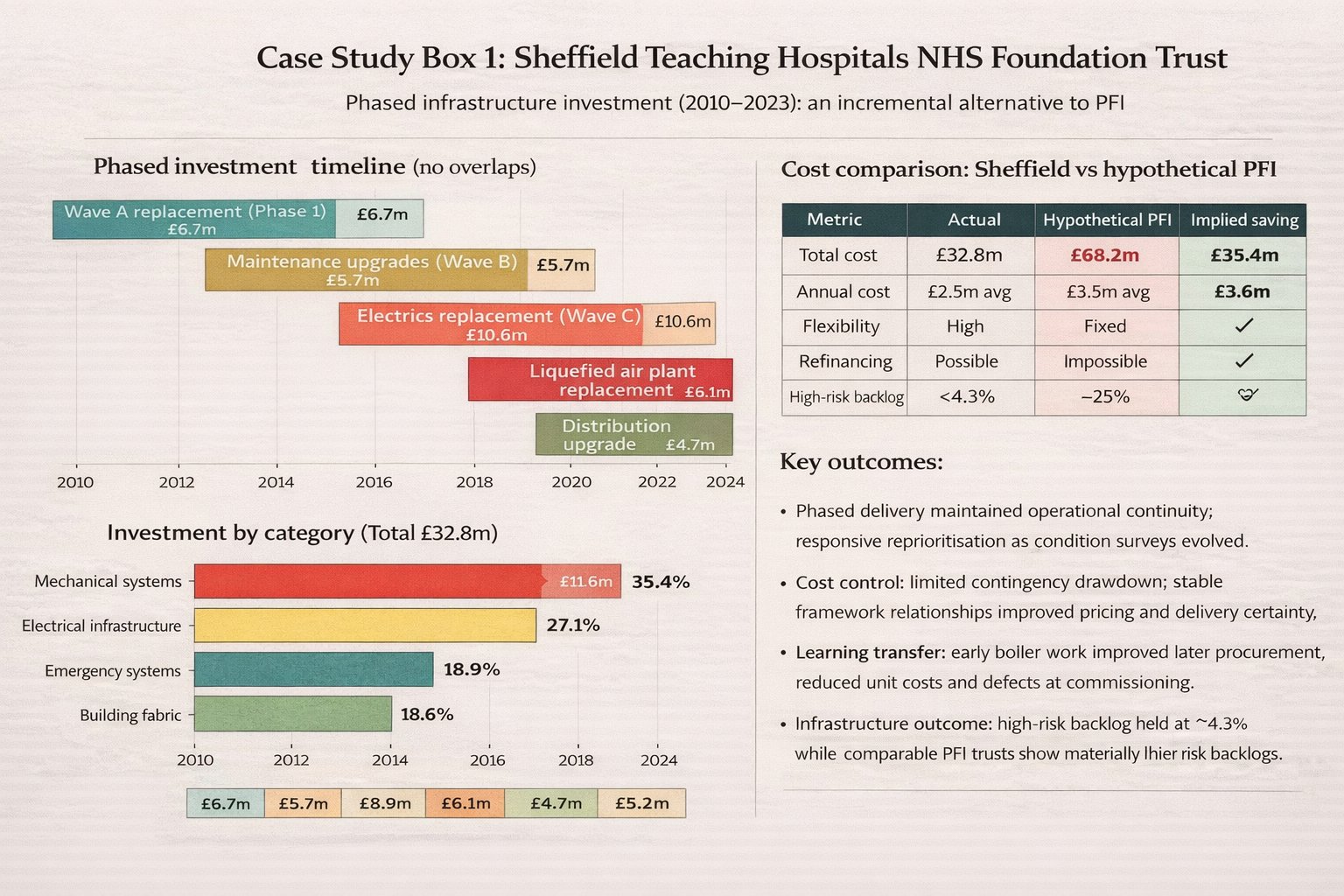

Incremental Capital Investment: The Sheffield Model

Incremental capital investment offers particular advantages for the distributed infrastructure needs that constitute the majority of NHS capital requirements, though it attracts less political attention than major new hospital announcements. Rather than locking annual payments into inflexible long-term contracts that constrain future flexibility, incremental approaches allocate capital on a rolling multi-year basis for phased construction and renovation that allows adjustment to changing priorities and clinical service evolution.

Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust illustrates this path through its actual infrastructure trajectory. With only £3.3 million in annual PFI burden versus Barts' £60 million, Sheffield achieved a high-risk backlog of just 4.3 percent compared to Barts' thirty-six percent despite operating a similarly complex acute hospital estate serving a large urban population with teaching hospital obligations. Sheffield's approach involved phasing infrastructure investment across multiple systems incrementally—upgrading heating and cooling capacity in distinct phases across several years, systematically replacing roofing across different buildings as budget allowed, modernizing electrical distribution in stages that minimized operational disruption—rather than attempting to address all infrastructure needs simultaneously through a single large capital program.

This incremental approach reduces operational disruption because work can be sequenced to avoid simultaneous major projects in clinically adjacent areas. It maintains flexibility to adjust priorities as clinical services evolve—if a hospital reconfigures stroke services or changes its maternity provision model, incremental capital allows redirecting planned investment to match the new service configuration rather than being locked into infrastructure suited to the previous model. It enables learning across phases, with early work informing later projects through feedback on what specifications and approaches worked best in practice. And crucially, it prevents the capital crowding-out that PFI creates, where large fixed payments for one scheme absorb capacity that could address emerging needs elsewhere in the estate.

Case Study Box 1 - Sheffield Teaching Hospitals: Phased Infrastructure Investment 2010-2025

For a rural district general hospital with £20 million total backlog, £2 million in annual capital allocation allows systematic addressing of needs over a decade while preserving ability to adjust priorities as clinical services evolve. Year one might focus on replacing the boiler plant that engineering surveys identify as highest immediate risk. Year two could address roof waterproofing across the main hospital building to prevent escalating water ingress damage. Year three might modernize electrical distribution in the aging wing housing surgical theatres. This sequencing allows each project to be specified precisely for current needs rather than attempting to predict requirements decades in advance, reduces financing costs by avoiding need to borrow for projects that won't be constructed until future years, and maintains flexibility to respond to unforeseen needs that emerge.

The barrier to incremental capital for smaller trusts isn't economic viability—the projects themselves are clearly necessary and would be less expensive financed through phased public capital than through bundled PFI contracts. The barrier is reliability of multi-year capital settlements. Trusts can plan and execute phased investment programs, but they need confidence that this year's £2 million allocation won't become next year's £500,000 when Treasury imposes emergency capital constraints to meet other fiscal pressures. The annual capital allocation chaos that NHS providers describe—with systems uncertain about capital availability until the financial year has begun, forcing hurried project development and inefficient procurement—makes incremental approaches nearly impossible to execute effectively.

Solving this requires committing to genuine multi-year capital settlements that trusts can rely on for planning purposes, accepting that this means Treasury surrendering some year-to-year flexibility to reallocate capital between priorities. The efficiency gains from allowing trusts to plan properly, procure effectively, and sequence work optimally likely exceed the value of maintaining Treasury's ability to raid capital budgets when short-term revenue pressures emerge. However, achieving this requires changing the institutional incentives that currently make capital budget raids attractive—Treasury can meet immediate revenue pressures through one-time capital reallocation while deferring the infrastructure consequences for future years when different officials will manage those problems.

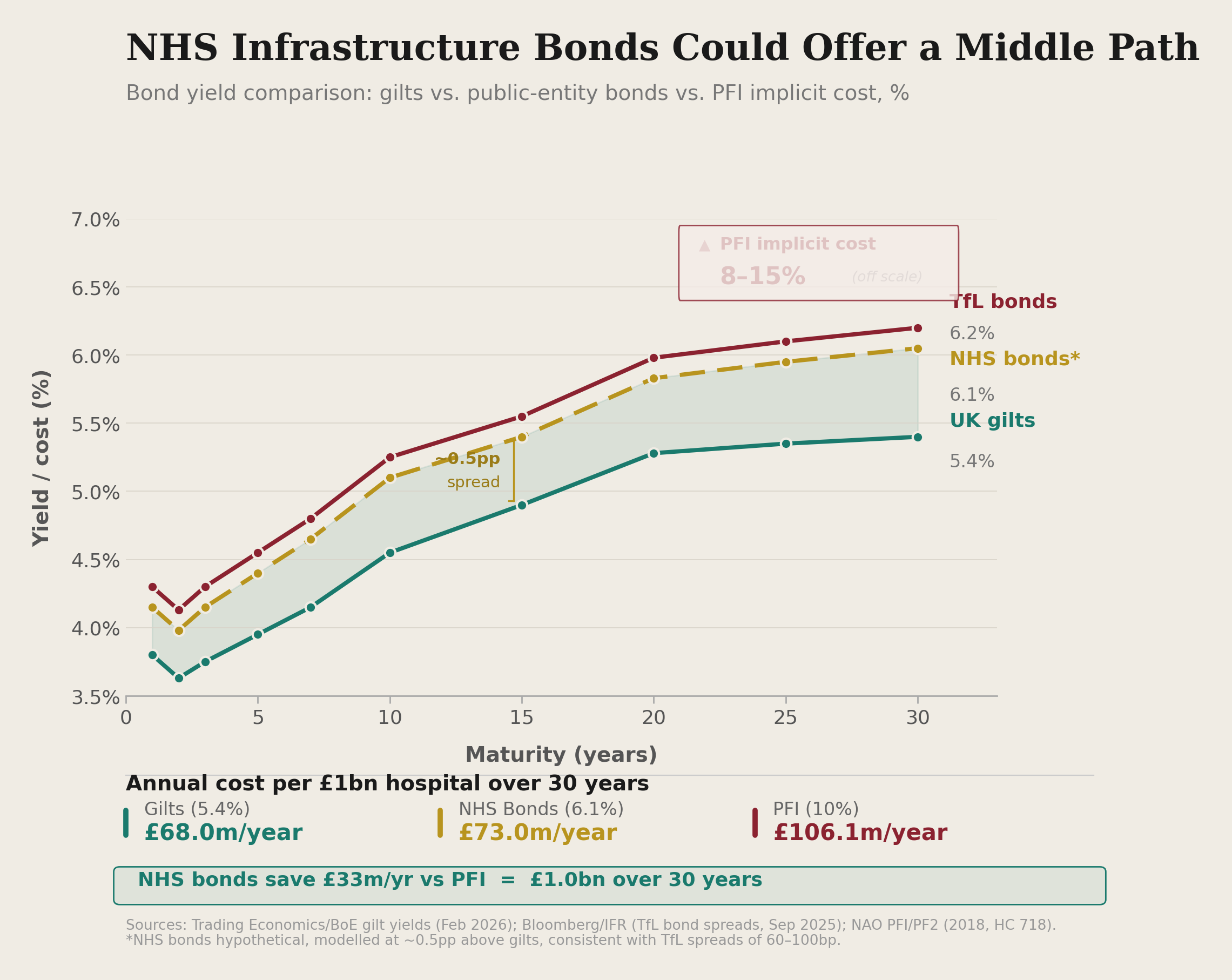

NHS Infrastructure Bonds: The TfL Model

NHS infrastructure bonds could provide transparent public sector access to capital markets at reasonable cost, representing a middle path between conventional government borrowing and private finance that potentially offers advantages of both. Rather than complex special purpose vehicles and inflexible contracts that characterize PFI, NHS trusts or a dedicated NHS Infrastructure Bank could issue bonds directly into capital markets, similar to the successful bond financing that Transport for London has employed for transport infrastructure or the municipal bonds widely used in the United States for local government capital investment.

The mechanics would involve an NHS entity—either individual foundation trusts with sufficient scale or a centralized NHS Infrastructure Bank acting on behalf of multiple trusts—issuing bonds with defined terms (maturity dates, coupon payments, credit rating, security provisions) into wholesale bond markets where institutional investors purchase them. Borrowing costs would range from four to six percent depending on credit rating and market conditions, substantially below PFI's eight to fifteen percent implicit cost but modestly above government's direct borrowing cost of three to four percent. The premium over government borrowing reflects investors' assessment that NHS entity debt carries marginally higher risk than sovereign debt because NHS entities could theoretically default while the UK government cannot default on sterling-denominated debt that it can ultimately print currency to repay.

Chart 4 - Bond Yield Curve Comparison: UK Gilts vs. TfL Bonds vs. Hypothetical NHS Infrastructure Bonds

Institutional investors—pension funds, insurance companies, sovereign wealth funds, asset managers—seek standardized, liquid securities in minimum denominations that facilitate portfolio management. A large teaching hospital needing £400 million for a major redevelopment could issue a bond with sufficient scale and standardization to attract investor interest. The bond would trade in secondary markets allowing investors to sell their holdings before maturity if needed, creating the liquidity that makes bonds attractive compared to illiquid private equity commitments. The hospital would service the bond through regular coupon payments (typically semi-annual) and repay principal at maturity, with the accounting treatment straightforward—the debt appears on the hospital balance sheet because the hospital controls the asset and bears repayment obligation.

However, individual DGH's seeking £30 million for distributed infrastructure investment might struggle with bond economics. Bond issuance carries substantial fixed costs—legal documentation to specify terms and comply with securities regulations, credit rating assessment by agencies like Moody's or Standard & Poor's to inform investor decisions, marketing to institutional investors through roadshows and prospectus distribution, ongoing compliance and reporting requirements throughout the bond's life. These costs might represent one to two percent of a £400 million issue but could easily reach five to eight percent of a £30 million issue, substantially increasing the effective borrowing cost and potentially eliminating the advantage versus direct government borrowing.

The solution to this scale problem exists in pooled bond vehicles that the US municipal bond market uses successfully for small local authorities. Rather than individual hospitals issuing their own bonds, an NHS Infrastructure Bank or similar entity could issue bonds against a portfolio of smaller trust investments. Under this model, twenty rural district general hospitals each requiring £30 million could collectively support a £600 million bond issue managed by the central NHS infrastructure entity. The bond would be secured against the diversified revenue streams of multiple trusts, reducing individual trust risk through portfolio diversification and providing the scale and liquidity that institutional investors require. Transaction costs would be shared across the pool, dramatically improving economics for individual trusts while maintaining access to capital market discipline that might improve project governance.

The barrier to NHS infrastructure bonds is institutional and political rather than economic. Creating a pooled bond vehicle requires legislative framework to establish the NHS Infrastructure Bank with appropriate legal powers, regulatory oversight to ensure prudent lending standards and protect public interest, operational infrastructure including credit assessment capabilities and bond management expertise, and crucially, Treasury acceptance of an NHS entity operating with genuine independence in capital markets. This last requirement represents the fundamental political challenge: Treasury has historically resisted allowing NHS entities to access capital markets independently precisely because it transfers capital allocation decisions from central government to organizational management, potentially committing future resources in ways that constrain future governments' fiscal flexibility.

Public-Public Partnerships: Retaining PFI's Benefits Without Private Finance

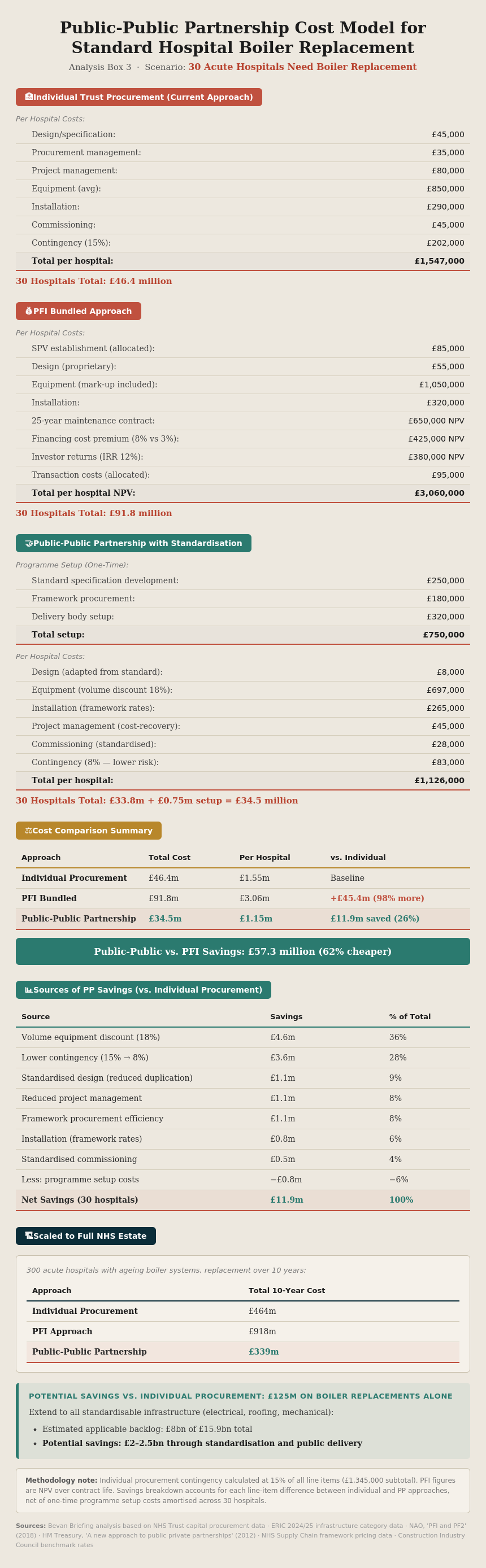

Public-public partnerships could deliver PFI's claimed project management benefits without premium private finance by retaining professional delivery capabilities while replacing expensive private capital with cheaper public borrowing. The core concept separates two things that PFI bundled together: project delivery expertise (valuable) and private finance (expensive). An NHS Infrastructure Bank or similar public entity would finance construction through government borrowing at three to four percent, a public sector delivery partner would manage projects using competitive procurement for actual construction work, and NHS trusts would own assets from day one rather than waiting for contract expiry.

For smaller trusts lacking internal capital project management capacity, this structure provides professional capability at cost without fifteen to sixty percent investor returns. A DGH with four hundred beds might have minimal in-house estates expertise beyond basic operational maintenance. When facing a £40 million infrastructure program spanning electrical upgrades, heating system replacement, and building fabric repairs, the trust needs professional project management, cost control, risk management, and technical oversight. PFI provided these capabilities (at extortionate cost), but the capabilities themselves are valuable regardless of financing source.

A public-public partnership separates these functions. The NHS Infrastructure Bank provides capital at government borrowing rates. A public sector delivery body (potentially a reconstituted NHS Estates or new NHS Infrastructure Delivery Service) provides project management expertise at cost-recovery rates rather than profit-maximizing prices. The trust receives professional delivery capability without investor returns, flexibility to adjust specifications as projects proceed rather than being locked into decades-old designs, and ownership of assets from the beginning rather than after thirty years of premium payments.

The structure enables standardization across common infrastructure needs in ways that PFI promised but never delivered. When thirty district hospitals across England all need to replace aging boiler plants over the next five years, a public sector delivery body can develop standardized specifications that reflect best practice in heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems for acute hospitals. Rather than each trust independently specifying boilers and paying for separate engineering design, the standardized approach dramatically reduces design costs while ensuring all trusts receive equipment that meets evidence-based performance standards. The delivery body can negotiate framework agreements with equipment suppliers for volume pricing that no individual trust could achieve, further reducing costs through genuine economies of scale.

Analysis Box 3 - Public-Public Partnership Cost Model for Standard Hospital Boiler Replacement

PFI companies claimed to offer these benefits through standardized designs and volume procurement, but never delivered them at scale because each PFI special purpose vehicle operated independently to maximize returns rather than genuinely sharing learning across projects. Competition between PFI consortia meant that successful approaches developed in one project remained proprietary rather than being shared across the NHS estate. A genuinely public delivery body could achieve actual standardization and systematic learning across projects because its mandate would be optimizing outcomes for the NHS rather than maximizing investor returns.

The barrier to public-public partnerships is primarily institutional capacity rather than economics or political resistance. Creating a public sector delivery body requires assembling technical expertise in hospital design, construction project management, facilities engineering, and commercial procurement. This expertise exists within the NHS and construction sector—the question is organizational structure to deploy it effectively. The model would likely start small with a few standardized infrastructure types (boiler plants, electrical distribution upgrades, roofing programs) where template solutions are most applicable, gradually expanding scope as the delivery body demonstrates value and builds capability.

Multi-Year Capital Settlements: Enabling Planning

Multi-year capital settlements work uniformly well across all trust types but prove particularly beneficial for smaller organizations with limited internal planning capacity. Current annual capital allocation chaos creates planning paralysis. Large teaching hospitals at least have significant internal finance teams that can rapidly pivot when capital allocations change—maintaining portfolios of investment options at varying stages of development, adjusting plans when budget news arrives, managing complex approval processes across multiple governance levels. Smaller rural trusts with limited planning capacity find annual uncertainty devastating because they lack the internal resources to maintain multiple contingency plans and rapidly revise specifications when budget allocations shift.

Multi-year settlements providing three to five year forward visibility would allow trusts to plan phased infrastructure investment properly, secure contractor availability during optimal windows rather than rushing to spend budget by year-end, and sequence projects for minimal operational disruption knowing that this year's electrical work can be followed by next year's heating upgrades without emergency reprioritization if next year's budget fails to materialize. The current three-year "baseline allocations" in capital guidance represent progress toward this model, but they're undermined by substantial performance-related elements and reserve allocations that create ongoing uncertainty about actual available capital until the financial year begins.