The Bevan Briefing #7 - The Budget Aftermath: Payment Reform, PFI Redux, and the New Old Foundation Trusts

Happy Christmas pals. As most people reach the final working day of the year I wanted to wish you a relaxing time off; although I gather there are many health bids going on over Christmas in which case I wish you quick and insightful responses to CQs and that Word formating doesn't conspire against you 20 minutes before submission.

As for my plans -

Actually no, with 2 small kids I'll be embodying all the faces of David Schitt and hiding.

The things which I've been noodling on for the past fortnight are

- The Health Foundations productivity commission call for evidence which I submitted my 4 ideas for https://www.health.org.uk/funding-and-partnerships/programmes/nhs-productivity-commission-call-for-evidence

- The new HDRS - I've also submitted my thoughts on the new service and the foundational things which need to be fixed for it to be a sucess - I am really excited about it.

- The budget - obviously. Thoughts on that further down the page....

- The press releases on the new and improved and definately very different Foundation Trusts proposed by team Milburn. Which are very different to the old ones also crafted by Alan Milburn.

Terrifyingly Honest: When Even the Man with the Plan Admits It's "Absolutely Terrifying"

When the chief executive of NHS England tells a room full of health leaders that the scale of planned changes is "absolutely terrifying," it's worth paying attention. Sir Jim's candid admission at the King's Fund annual conference wasn't about winter pressures or waiting lists. It was about something more fundamental: the NHS is about to undertake the most radical overhaul of its financial architecture in decades, at precisely the moment when it can least afford to get it wrong.

"When you look at all of the things that we're trying to change at once, I've never seen anything that big before," Mackey told the conference.[1] "It's all absolutely terrifying, when you put it all together and you see it as a package."

This wasn't hyperbole from someone given to exaggeration. This was the assessment of an ex-CFO who has seen multiple waves of NHS reorganisation, speaking after an NHS England board meeting that had clearly sobered even the optimists in the room. The changes he described—unbundling block contracts, phasing out deficit support, scrapping system control totals, moving to activity-based payments for emergency care—represent the most comprehensive reform of NHS payment mechanisms since Payment by Results was introduced over two decades ago.

But Mackey's moment of unguarded honesty raises an uncomfortable question: if the architect of these reforms finds them terrifying, what hope do the rest of us have?

The Budget: More Money, Same Problems

The Autumn Budget 2024 was supposed to mark a turning point. The Chancellor announced a £22.6 billion increase in NHS England's budget over two years—the largest cash injection since 2010, excluding pandemic spending.[2] In real terms, this represents average annual growth of around 4.2%, significantly above the austerity-era average of 1.6% but below what most analysts suggest is needed to get parts of the service back on its feet (backlog maintenance I'm looking at you...).[3]

The headlines were predictably triumphant. The NHS had been "saved." The crisis was "over." Ministers lined up to take credit for their generosity.

The reality, visible in the fine print and in the worried faces of finance directors across the country (supported by chat at the HfMA conference), was rather different.

First, the employer National Insurance increase announced in the same budget will cost the NHS an estimated £1.5 billion annually—money that comes straight back out of the settlement. [4] Giveth and taketh away.

Second, the settlement must cover existing commitments: the multi-year pay deals already agreed with NHS staff, the Agenda for Change uplifts, the consultant contract changes, and the junior doctors' settlement that may yet materialise. By some estimates, these commitments alone absorb 60-70% of the additional funding.[5]

Third, capital spending—the money needed to fix crumbling buildings, replace Victorian-era equipment in the backlog maintenance queue, and install the digital infrastructure everyone agrees is essential—received a modest uplift but nothing approaching the £10 billion maintenance backlog documented by NHS Providers.[6] The capital budget for 2025-26 stands at £13.6 billion, of which much is already committed to existing projects, including the repeatedly delayed New Hospital Programme. Which as sharp-eyed of you will notice, does not contain many new hospitals.

Fourth, and most tellingly, the settlement included precisely nothing for adult social care beyond existing commitments. The sector that everyone acknowledges is critical to reducing delayed discharges and preventing avoidable admissions received no additional support. The mythical "integration" of health and social care remains as distant as ever, not because anyone disputes its necessity, but because no government is willing to grasp the political and fiscal nettle of properly funding it. I think this is because anything which ends up being partly taxpayer funded directly ends up being politically toxic and gets kicked into the long grass.

What the budget revealed, in other words, is that we remain trapped in the same fundamental dynamic that has characterised NHS funding for fifteen years: enough money to avoid complete collapse, not enough to address underlying problems, and certainly not enough to fund the transformation everyone insists is necessary.

Payment Reform: All Risk, No Reward

It is against this backdrop that NHS England is attempting its "absolutely terrifying" payment reforms. The details, due to be published in the coming weeks, represent a wholesale reimagining of how money flows through the NHS.[7]

The centrepiece is the "unbundling of the block"—Mackey's phrase for dismantling the block contracts that have become standard since the pandemic. "The evil block contracts," he called them, with the zeal of a reformer who has seen the enemy and knows its name. "That's made us lose sight of what we're providing, commissioning, the data quality, the specificity and standards."

Block contracts, for the uninitiated, are fixed payments made to providers regardless of activity levels. They emerged in force as a pragmatic response to financial instability and were formalised during COVID-19 when normal commissioning arrangements became impossible. They have the virtue of simplicity and the vice of removing any link between funding and activity. A trust receives the same money whether it treats 100 patients or 1,000. They have been used for a long time to be the default for where units of activity are hard to quantify such as Mental Health and Community but we'd moved away from them in acute when PbR was mandated in the early '00s.

The proposed alternative is a return to activity-based payment, but with a twist. Rather than the crude "Payment by Results" tariffs of the past, NHS England envisages "blended contracts" that combine fixed elements with variable payments tied to activity and, eventually, outcomes.[8] For non-elective care, this means trusts will receive a base payment plus additional funding based on emergency admissions and, in theory, on their success in keeping people out of hospital.

The logic is appealing. If we want providers to focus on prevention and community care, the argument goes, we need to pay them for those things. If money follows the patient, providers have an incentive to improve quality and efficiency. The market will work its magic.

But this logic rests on several heroic assumptions, all of which deserve scrutiny.

First, it assumes that data systems are capable of tracking activity and outcomes with sufficient accuracy to make fair payments. Anyone who has worked with NHS data knows this is optimistic. Coding quality varies wildly between trusts. Emergency department data is notoriously unreliable. Community activity is captured inconsistently if at all. By this I mean that having all ICD10 codes and having anything over caseload and activity numbers is the exception. The very problems Mackey identifies—poor data quality, lack of specificity—are precisely what made block contracts necessary in the first place. Unbundling the block doesn't solve the data problem; it makes accurate data an absolute precondition for avoiding financial chaos.

Second, it assumes that trusts have the capacity to respond to financial incentives. In theory, if a trust loses money when patients are admitted as emergencies, it will invest in community services to prevent those admissions. In practice, trusts cannot cut hospital capacity without destabilising emergency care, cannot invest in community services they don't control, and cannot overcome the social determinants and system fragmentation that drive avoidable admissions. The payment mechanism changes, but the underlying constraints remain. The vagueries around data definitions on the outcomes are going to be a key restriction.

Third, and most fundamentally, it assumes that the total quantum of money in the system is adequate. This is the fatal flaw in the entire edifice. Payment reform, at its core, is about redistribution: taking money from one part of the system and giving it to another. But if the system as a whole is underfunded, redistribution becomes a zero-sum game. Every winner requires a loser. Every trust that succeeds in preventing admissions takes money from another trust's emergency department. The incentives point in the right direction, but the aggregate effect is simply to reshuffle deck chairs on a sinking ship.

Mackey, to his credit, is not blind to these risks. "The pace at which we can make all of these changes together is going to have to be managed," he acknowledged.[1] He is "a bit worried" about shifting funding out of hospitals "because I've been around this a few times." The unbundling process must ensure "the gearing works so that it is actually achievable to do important, necessary things to keep people out of the hospital."

But worry is not a strategy. And the track record of managed financial transitions in the NHS is not encouraging.

The most immediate concern is what happens to trusts that are already in deficit. Under the proposed reforms, deficit support—the additional funding provided to trusts that overspend—is being phased out.[7] The theory is that removing the safety net will force trusts to live within their means. The reality is that many trusts are in deficit not because of poor management but because of structural factors: outdated buildings, expensive PFI contracts, historic underfunding of capital, or the simple mismatch between the cost of providing services and the funding received.

Removing deficit support from such trusts doesn't create efficiency; it creates impossibility. Finance directors will be forced to cut services, reduce quality, or accumulate debt. None of these options is acceptable, but all may become necessary when the payment system demands financial balance that the underlying resources cannot support.

We are likely to see many finance leaders moving on if the stratagem (if you can call it that) of financial balance at all costs is taken to its full conclusion.

The Productivity Paradox: Diagnosed to Death

And here's where the picture gets even more complicated. The government has set an ambitious target of 2% annual NHS productivity growth to the end of this parliament—more than double the historical average.[9] This target underpins much of the fiscal arithmetic in the spending review. If productivity doesn't grow at this rate, either the NHS will need billions more in funding or care standards will decline.

But there's a problem. The Health Foundation recently convened a group of 14 experts with research, policy and front-line experience to assess the likelihood of meeting this target. Their verdict was sobering: they judged there is only a 1 in 6 chance (roughly 15%) of achieving the government's 2% annual productivity growth target under current conditions.[10]

The reasons for this pessimism are well-documented in the NHS Productivity Commission's report, From Diagnosis to Delivery.[11] NHS productivity rose for decades before COVID-19, but fell sharply in 2020 and has not recovered its original trajectory. According to the Office for National Statistics, if pre-pandemic trends had continued, the NHS would have been around 14% more productive in 2022/23—equivalent to roughly £20 billion of additional care.

What drove productivity growth in the past? The Commission identifies a critical factor: shorter hospital stays. Enabled by technological innovation, advances in treatments, and changes to payment systems, the average length of a hospital stay fell from 8.4 days in 2000/01 to 4.5 days in 2018/19.[11] The Commission's analysis shows that if average length of stay had remained constant at 2000/01 levels, half the total gains in non-quality-adjusted productivity up to 2018/19 would have been eliminated.

But this trend has reversed. Hospital stays lengthened during the pandemic and haven't fully recovered. Meanwhile, the UK entered the pandemic with low bed capacity and high bed occupancy compared to peer countries—a combination that amplifies the productivity impact of longer stays.[11]

The Commission identifies four key drivers that must be strengthened to achieve sustained productivity growth:

Workforce: The NHS needs the right skills to meet changing demand, with clinical time focused on clinical care rather than administration. But staff absence rates have risen across England, reaching particularly high levels in some regions (5.6% in the North West compared to 4.3% in the South East in April 2025).[11] We are missing a workforce plan and engagement with higher education to make it feasible.

Capital: Modern, reliable infrastructure—scanners, theatres, IT and estates—improves patient safety and flow. But capital per worker has fallen by 36% in real terms since 2010.[11] During the 2010s, the UK would have needed to invest £32.9 billion more to match spending of comparable countries.

Technology and innovation: Breakthroughs in AI and digital health show genuine promise, but most organisations across the economy struggle to capitalise on technology. Only 70% of integrated care systems have electronic bed management systems, and fewer than 40% report seeing benefits.[11]

Transformation: Leadership, management, governance and incentive environments that set direction and align action. But 60% of NHS trusts have a 'first-time' CEO,[11] and acute care has accounted for a growing share of NHS spend over the past two decades—from around 50% in 2002 to over 55% by 2021, even as policy consistently advocates for a shift to community and primary care.[12]

The Commission warns of a risk: attempting to meet a short-term productivity target could crowd out longer-term priorities. The last time the NHS achieved 2% annual productivity growth (non-quality adjusted) was in the early 2010s (2009/10 to 2014/15), and subsequent growth was much weaker (0.3% from 2014/15 to 2018/19).[11]

As the Commission puts it: "The risk... is 'diagnosis without delivery': repeated identification of barriers and solutions but without execution."[11]

The Return of PFI: Private Finance, Public Fleecing

If payment reform represents the NHS's attempt to solve current problems through financial engineering, the New Hospital Programme represents its determination to repeat past mistakes with fresh enthusiasm.

I want to make it clear before we go any further that I am not against private sector involvement in the NHS. There is a time and place for most things including outside support. However there were a series of massive fucking own goals which happened as part of PFI #1 which seem set to make a come back.

The programme, announced with great fanfare in 2019, promised 40 new hospitals by 2030. It has since been scaled back, delayed, and repriced multiple times. The current estimate is that around 32 hospital building projects will be completed, at an updated cost significantly higher than originally projected, over a timeline that extends well beyond the original deadline.

The financing model for many of these projects relies on what the government carefully avoids calling PFI but which bears all the hallmarks of its predecessor. The preferred terms are "innovative financing," "public-private partnerships," or "private sector capital." The substance is the same: private companies finance construction in exchange for long-term repayment contracts that commit future NHS budgets for decades.

The Banking Bonanza (or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love 15-25% Returns)

The history of PFI in the NHS is well documented and universally acknowledged as a disaster. But what is less frequently discussed is just how profitable PFI proved for the financial sector—and why banks were so enthusiastic about these schemes.

The numbers are staggering. According to research by the Centre for Health and the Public Interest, PFI companies made pre-tax profits of £1.9 billion from 99 NHS contracts between 2004 and 2021, with an additional £1.07 billion paid out in dividends.[13] Directors' fees alone totalled £47.6 million. But these figures tell only part of the story.

Banks made extraordinary returns on PFI deals. Academic research published in the BMJ found that shareholders in PFI schemes could expect real returns of 15-25% per year—vastly higher than typical infrastructure project returns of 1-2%.[14] Some reports suggested profits reached 40-70% in annual returns. The European Union Services Strategy Unit calculated that average profit for banks in PFI projects exceeded 50%.[15]

These extraordinary profit margins explain why major banks created dedicated PFI divisions. Barclays, for instance, advertised on its corporate website its "dedicated team with extensive experience working with Foundation Trusts, GPs, and on PFI and LIFT transactions."[16] HSBC went further, creating HSBC Infrastructure Company Ltd (HICL) and becoming the first UK company to take PFI offshore when it registered the HICL fund in Guernsey.[17] Through various vehicles, HSBC came to own at least three NHS hospitals outright—in Barnet, Central Middlesex, and Stoke Mandeville.

The profit mechanisms were multiple and overlapping. Banks charged interest rates double those of ordinary government borrowing. They arranged the deals and took arrangement fees. They provided senior debt to Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs) and charged interest. They held equity stakes and extracted dividends. They refinanced deals in secondary markets, making windfall profits by selling on contracts at inflated prices. And crucially, all of this was insulated from normal business risk because the government effectively guaranteed the income stream.

The University College London Hospital (UCLH) PFI provides a particularly egregious example: 50% of the PFI company's turnover was recorded as profit before tax, and it paid out £200 million in dividends.[17] Meanwhile, the trust struggles with annual PFI payments that have risen to over £40 million, including £40 million per year in interest payments alone.

The Taxpayer Pays

The costs to the NHS are devastating. IPPR analysis found that for just £13 billion of actual capital investment, the NHS had been saddled with an £80 billion repayment bill.[18] The Nuffield Trust notes that total PFI repayments cost around £2.1 billion per year and will reach a peak of £2.7 billion in 2029-30.[19] Some trusts spend up to 20% of their operating budget on PFI payments.

Barts Health NHS Foundation Trust, opened its new buildings in 2012 under a PFI contract that requires annual payments of around £150 million—roughly 10% of the trust's entire income. These payments continue regardless of how the trust performs, how many patients it treats, or what happens to NHS funding. The contract runs until 2048. Every finance director at Barts since 2012 has identified PFI as the single biggest obstacle to financial sustainability, yet there is no escape clause, no mechanism for renegotiation, and no prospect of early termination.

Similar stories play out across the country. St Thomas' Hospital in London, the Northern General in Sheffield, the Queen Elizabeth in Birmingham—all are saddled with PFI contracts that consume vast sums that don't represent value for money. The ironclad contracts mean that even when trusts face financial crisis, the PFI payments continue. Staff can be cut, services can be reduced, but the contract must be honoured.

There are many in the same boat which is why it's completely bonkers that this is the best that they can come up with to finance necessary upgrades and also that there's no national negotiation department to stand up to the banks who churn through these negotiations at a national level. For most people, they will do a PFI in a career so it makes sense (to me at least) to have that information and expertise centralised. Especially given the sums involved.

And the taxpayer bears all the risk. Research by the Centre for Health and the Public Interest shows that the NHS bears the risk of inflation: annual PFI payments rise automatically with the Retail Price Index, regardless of whether the PFI companies' costs increase by the same rate.[20] This added an additional £470 million to NHS PFI bills in just two years (2022-24) when inflation spiked. The National Audit Office has documented multiple cases where trusts signed deals they could not afford, where construction was delivered late and over-budget, and where the public sector was forced to bail out failing projects.[21]

Why Governments Keep Doing It

The political economy of why governments keep returning to PFI despite its documented failures is grimly straightforward. Capital spending appears on the government's balance sheet. It counts toward borrowing targets and debt ratios. It is visible and must be justified to voters and markets. Private finance, if structured correctly, does not. It allows governments to build infrastructure without taking on debt, to announce major projects without finding the money, and to transfer the political costs to future administrations. It's shadow debt.

The Treasury rules that incentivise this behaviour have not changed. The fiscal constraints that made PFI attractive in the 1990s and 2000s remain in force. And so the cycle repeats: a government announces ambitious hospital building, finds it cannot or will not provide public financing, turns to private capital with reluctance or enthusiasm depending on its ideological disposition, and signs contracts that will haunt the NHS for generations.

The rebranding is unconvincing. The "innovative financing" for the New Hospital Programme may include more flexible terms, better risk-sharing, or improved value-for-money mechanisms. But the fundamental trade-off—capital now in exchange for revenue commitments later—is unchanged. And in a system where revenue budgets are already stretched to breaking point, every pound committed to servicing construction debt is a pound unavailable for staffing, equipment, or patient care.

The banks, of course, understand this perfectly well. They created dedicated divisions precisely because PFI was so profitable. Barclays' separate department for healthcare PFI deals was not an act of public service—it was recognition that lending to the NHS at double government borrowing rates, with government-guaranteed repayment, was one of the safest and most lucrative investments available.

When the private sector makes 15-25% annual returns on infrastructure that the Treasury could finance at 3-3.5% (the cost of PDC), the question is not whether this represents value for money. The question is: who benefits, and who pays?

Foundation Trusts: The Autonomy That Never Was (And Never Will Be)

The payment reforms and PFI redux take place within a governance structure that was itself supposed to solve these problems. Foundation trusts, introduced between 2003 and 2006, were conceived as the answer to NHS micromanagement. They would be independent organisations, free from day-to-day Whitehall control, accountable to local governors and members rather than distant bureaucrats. They would have the freedom to innovate, to respond to local needs, and to manage their affairs without ministerial interference.

The vision was compelling. The reality has been rather different.

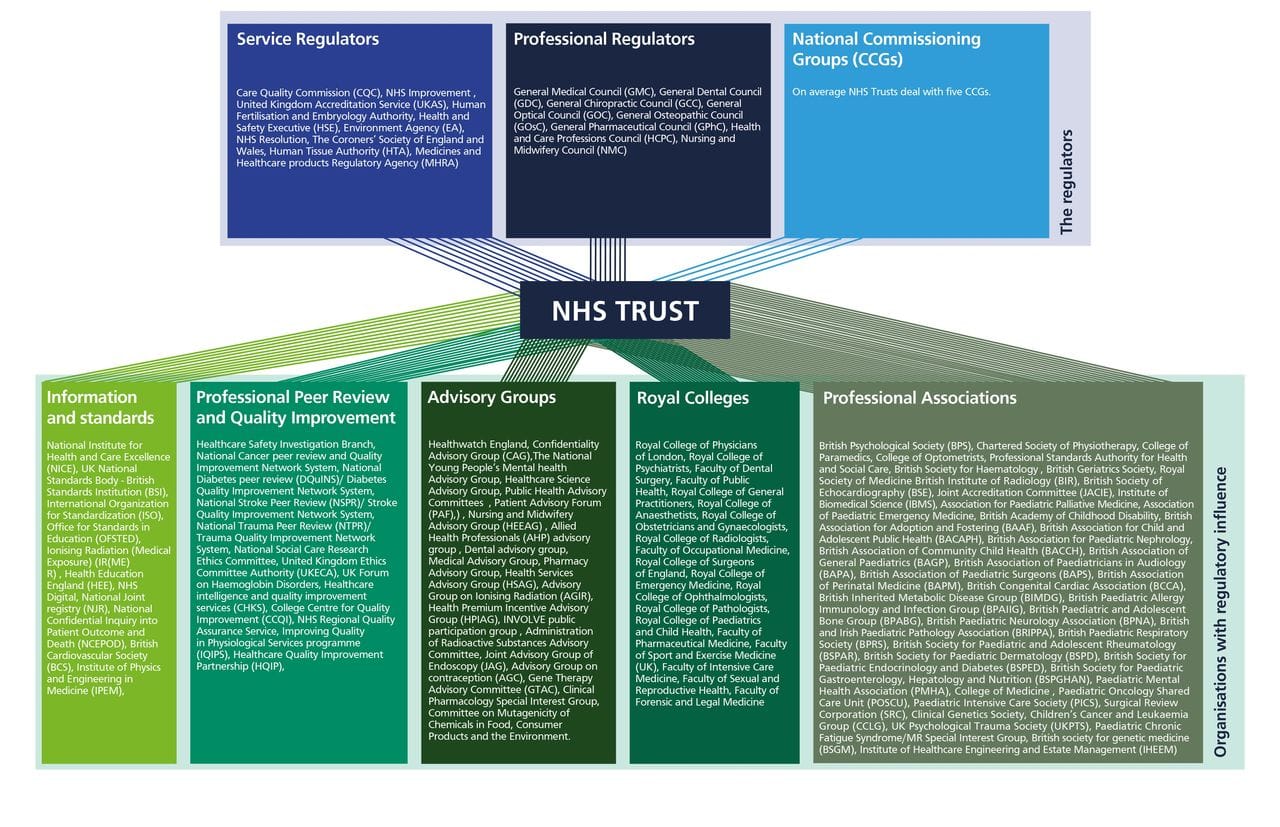

Today's foundation trusts operate under intense oversight from NHS England regions, integrated care boards, the Care Quality Commission, and various other regulatory bodies. They must comply with operational planning guidance, system financial envelopes, and centrally determined targets. They participate in integrated care systems where their autonomy is explicitly subordinated to system priorities. Their capital spending requires approval, their service changes are subject to review, and their financial performance is monitored in granular detail.

As you'll see below - it's still an absolute mess.

https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/9/7/e028663

The regulatory framework has expanded steadily since foundation status was introduced. "Earned autonomy"—the principle that high-performing trusts would gain more freedom—has been quietly forgotten. Instead, the ratchet has turned in one direction only: toward greater central control, more detailed requirements, and less scope for local discretion.

The most recent addition to this framework is the integrated care system statutory duties introduced in 2022. ICBs are required to manage their system budgets and meet system-level targets. Trusts within each system are expected to collaborate, to subordinate institutional interests to system priorities, and to accept collective accountability for performance. The system control totals that Mackey's reforms are scrapping were the financial manifestation of this collective accountability: each trust received a target, but the system as a whole was judged on aggregate performance.

The contradiction is obvious. Foundation trusts are legally independent organisations with their own boards, members, and governors. They are required to manage their finances, maintain service quality, and respond to their local populations. But they are also required to function as component parts of integrated systems, to accept resource allocation decisions made at system level, and to sacrifice organisational autonomy for system benefit.

This tension creates governance problems that nobody has seriously attempted to resolve yet. When a foundation trust board makes a decision that conflicts with system priorities, who has ultimate authority? When system financial pressures require service reconfiguration that a trust's governors oppose, what is the legal position? When accountability for failure is distributed across a system, how can individual boards fulfil their statutory duties?

The honest answer would be to acknowledge that foundation trust status, as originally conceived, is incompatible with the integrated system model that NHS England is now pursuing. Either trusts are independent organisations with genuine autonomy, or they are components of managed systems with collective accountability. They cannot meaningfully be both.

But honesty would require legislation, political capital, and a willingness to have difficult conversations about what kind of NHS we actually want. It is easier to maintain the fiction of foundation trust autonomy while exercising de facto central control through planning guidance, financial levers, and regulatory pressure.

Of course there could be a cunning plan to balance all of these things out but based on what's out there at the moment, I can't see how this is all going to be squared away.

Advanced Foundation Trusts: The Elite Tier Nobody Asked For

Into this confused landscape comes the government's latest wheeze: "advanced foundation trust" status. Announced in November 2024, the scheme promises to reward the NHS's "best-run hospitals and community health trusts" with "more independence" and freedom from "central bureaucracy."[22]

Health Secretary Wes Streeting described this as "a major shift in how the NHS is run, ending decades of top-down control." Eight trusts have been nominated for assessment: Berkshire Healthcare, Dorset Healthcare, Central London Community Healthcare, Northamptonshire Healthcare, Northumbria Healthcare, Alder Hey Children's, Norfolk Community Health and Care, and Cambridgeshire Community Services.

The proposal echoes previous attempts at "earned autonomy"—the repeatedly failed promise that high-performing organisations would gain freedom if only they could prove themselves worthy. The premise is seductive: reward excellence, cut red tape for those who demonstrate competence, let the best organisations innovate while maintaining oversight of struggling ones.

But scratch the surface and familiar problems emerge. What does "more independence" actually mean when trusts remain subject to ICB oversight, NHS England planning guidance, CQC regulation, and statutory duties? The press release promises trusts can "speed up processes on improvements, including buying new scanners quicker or improving wards" if they have built up savings. But capital spending still requires approval, and most trusts don't have savings—they have deficits and PFI obligations.

The announcement explicitly states that advanced foundation trusts will be "expected to deliver faster improvements in patient care, waiting times and productivity" and to "help drive positive change across the wider NHS."[22] In other words, greater freedom comes with greater demands. This is not autonomy; it's a bargain in which trusts trade additional performance commitments for marginally reduced bureaucracy.

Moreover, the timing is curious. The government is simultaneously unbundling block contracts, phasing out deficit support, and setting ambitious productivity targets. Trusts will be navigating unprecedented financial and operational change. Offering a handful of organisations slightly more freedom while the entire system undergoes radical reform feels like rearranging deck chairs—except in this case, the deck chairs might be bolted to the floor anyway. And on the Titanic.

The international evidence on granting autonomy to high-performing providers is mixed at best. Studies from the Netherlands and Sweden suggest that organisational autonomy can improve efficiency when paired with genuine financial independence, adequate capital, and functioning competition or contestability.[23] But those conditions don't exist in the English NHS. What we're seeing instead is symbolic autonomy—freedom to make decisions within parameters so tightly constrained that the choices available barely matter.

And there's a darker possibility. If advanced foundation trust status becomes the new aspiration, it creates a tier system where the "deserving" trusts gain privileges while others face greater restriction. This could exacerbate inequalities: well-funded trusts in affluent areas with strong leadership already perform better; giving them additional advantages while struggling trusts—often in deprived areas with worse infrastructure—face tighter oversight risks widening rather than closing performance gaps.

The NHS Productivity Commission warns against precisely this kind of short-termism: "There is also a risk that a short-term target crowds out longer term priorities."[11] Advanced foundation trust status might boost performance metrics for elite organisations in the short run. But if it doesn't address the fundamental barriers to productivity—workforce retention, capital investment, technology adoption, and system-wide transformation—it becomes another announcement without impact.

The Accountability Shell Game

These three developments—payment reform, PFI financing, and foundation trust governance (now with added "advanced" status)—are connected by a common thread: the desire to exercise control without accepting responsibility.

Central government wants to determine NHS priorities, allocate resources, and claim credit for improvements. But it does not want to be held accountable when things go wrong. And so it creates structures that distribute responsibility while concentrating power.

Payment reform shifts financial risk to providers while central bodies retain control over tariffs, planning assumptions, and the overall funding envelope. Trusts are told to live within their means, but the means are determined by others. When financial balance proves impossible, the blame falls on management rather than on the structural imbalance between resources and requirements.

PFI financing allows governments to build hospitals without increasing public debt, but it commits future NHS budgets to repayment schedules that future governments and managers cannot escape. The political credit for opening new facilities accrues to those who sign the contracts; the financial burden falls on those who must make the payments decades later. The banks extract extraordinary profits guaranteed by government, while trusts and patients bear the cost.

Foundation trust status creates the appearance of local accountability and organisational independence while the reality is centralised control through regulatory oversight and system requirements. When trusts fail to meet targets or experience quality problems, boards can be replaced and management can be criticised. But the system-level decisions that constrained those organisations are insulated from scrutiny.

Now add advanced foundation trust status: another layer of apparent autonomy that comes with additional performance expectations. Trusts that "succeed" gain marginal freedom; trusts that "fail" face greater restriction. But the fundamental accountability question remains unanswered: when a trust operates under ICB oversight, with centrally determined payment mechanisms, within a system control envelope, subject to national planning guidance, with capital budgets requiring approval, how much of its performance is genuinely under local control?

This is the accountability shell game: responsibility is always somewhere else, power is always elsewhere, and failure can always be attributed to implementation rather than design.

The consequences are visible throughout the NHS. Finance directors managing impossible budgets are told to be more efficient. Chief executives juggling competing priorities are told to show leadership. Frontline staff working understaffed shifts are told to maintain standards. And at every level, the implicit message is the same: if you cannot succeed with the resources provided, the problem is you, not the resources.

What Would Honesty Look Like? (Spoiler: Uncomfortable)

Mackey's moment of candour at the King's Fund conference was refreshing precisely because it was unusual. Senior NHS leaders rarely admit that the changes they are implementing are "absolutely terrifying." They present reforms with confidence, minimise risks, and promise that careful management will overcome difficulties.

But Mackey is right to be terrified. The scale of change contemplated is genuinely unprecedented. Unbundling block contracts, moving to activity-based payments, phasing out deficit support, and managing this transition alongside elective recovery targets, workforce shortages, productivity demands, negotiation of billions of national debt which continues for an average lifetime and continuing industrial action—any one of these would be challenging. Attempting all simultaneously, in a system already under extreme pressure, with inadequate resources and creaking infrastructure, is extraordinarily risky.

The question is not whether these changes could work in ideal conditions. In a well-funded system, with modern infrastructure, adequate capacity, and time to implement carefully, payment reform might drive beneficial changes. The question is whether they can work in the NHS as it actually exists: undercapitalised, understaffed, and operating at the edge of its capacity.

The honest answer is probably not. Or at least, not without casualties. Some trusts will fail. Some services will be cut. Some patients will experience worse care. The system may emerge stronger eventually, but the transition will be painful and the human cost will be real.

Honesty would also require acknowledging that some problems cannot be solved through financial engineering. Payment mechanisms matter, but they are not magic. They cannot create capacity that does not exist, overcome workforce shortages, or substitute for adequate funding. They cannot fix crumbling buildings or install modern IT systems. They cannot overcome the social determinants that drive health inequalities or the demographic trends that are increasing demand faster than the economy can grow resources.

International evidence is instructive here. The Netherlands, often cited as an example of successful activity-based payment, has health spending per capita roughly 30% higher than the UK.[24] The US, which has been experimenting with outcomes-based payment for over a decade through Accountable Care Organizations (Mr Stevens favourite import) and bundled payments, has seen modest improvements in some measures but no transformation in cost or quality. New Zealand attempted major payment reform in the 1990s, creating an internal market not unlike the one NHS England is recreating, and reversed course after the reforms increased costs without improving outcomes.

The lesson from these international comparisons is not that payment reform never works, but that it requires favourable conditions—you need headwinds going into it: adequate baseline funding, functioning data infrastructure, organisational capacity to respond to incentives, and time to implement carefully. The NHS currently has none of these.

The NHS Productivity Commission makes the same point more diplomatically: "To avoid a 'diagnosis without delivery' cycle, the NHS Productivity Commission will focus on four drivers where national policy can unlock gains: workforce, capital, technology and innovation, and transformation."[11] The implication is clear: without addressing these foundational issues, no amount of payment reform, productivity targets, or governance changes will deliver sustained improvement.

Honesty would require admitting that some problems are political rather than technical. The NHS is underfunded relative to comparable countries and relative to what the public expects from it. Social care is grossly underfunded, creating pressures that no amount of hospital payment reform can solve. Capital investment has been neglected for decades, creating a sizeable maintenance backlog and infrastructure deficit that constrains everything the NHS tries to do.

These are not problems that clever payment mechanisms can fix. They require political choices: higher taxes, or lower expectations, or both. They require long-term commitment to capital investment, to workforce planning, to social care funding. They require governments to accept that there is no magic solution, no reorganisation that will unlock vast efficiencies, no payment reform that will make scarcity disappear.

But such honesty is rare in health policy. It is politically difficult, intellectually unsatisfying, and tonally depressing. It is easier to announce reforms, to promise transformation, and to hope that this time will be different.

Managing the Terrifying

Sir Jim Mackey concluded his King's Fund remarks with characteristic pragmatism: "The counterfactual of not changing them is much worse, in which we could not have continued as we are. We really need to do this, but it's all about how we'll manage this together."[1]

He is probably right that the status quo is unsustainable. Block contracts have removed any link between funding and activity, creating perverse incentives and obscuring what is actually being purchased as well as reducing the biggest lever of data quality which is PbR. The financial architecture of the NHS has become so complex and divorced from operational reality that even finance directors struggle to explain it. I spent over 20,000 words unpacking it in simple terms and probably still missed some stuff. Something has to change.

But acknowledging that change is necessary does not mean any old change will do. The payment reforms NHS England is implementing carry real risks: destabilising trusts that are already fragile, creating winners and losers based on factors beyond their control, and failing to achieve the intended benefits because the preconditions for success are absent.

The same caution applies to hospital financing and foundation trust governance. Yes, capital investment is essential and public funding is constrained. But that does not make PFI-style contracts a good idea—particularly when banks have demonstrated they can extract 15-25% annual returns from arrangements that leave trusts crippled by debt. Yes, foundation trusts are in tension with integrated systems. But that does not mean the solution is to quietly abandon their autonomy while maintaining the legal fiction, or to create an elite tier of "advanced" trusts that gain marginal privileges while underlying problems remain unaddressed.

If these changes are to be "managed together," as Mackey suggests, it will require several things that are currently in short supply.

First, realistic timescales. The rush to implement payment reform in 2026-27 appears driven more by political cycles than operational reality. A more cautious approach—piloting changes, learning from early implementation, adjusting based on feedback—would reduce risks but require patience that politicians rarely demonstrate.

Second, adequate resources for transition. Moving from block contracts to activity-based payment will reveal mismatches between historic funding and actual costs. Some trusts will gain, others will lose. Managing this transition without destabilising essential services requires transitional funding to smooth the adjustment. The budget did not provide this.

Third, genuine engagement with frontline organisations. The repeated pattern in NHS reform is for changes to be designed centrally, announced confidently, and imposed regardless of operational concerns. Mackey's admission that the changes are "absolutely terrifying" should be the start of a conversation, not the end of one. Trust finance directors, ICB leads, and frontline clinicians should be partners in designing implementation, not recipients of guidance they had no role in creating.

Fourth, honest evaluation. Payment reforms should be monitored rigorously, with clear metrics for success and failure, and with a willingness to reverse course if they are not working. This requires independence from those implementing the reforms and protection from political pressure to claim success regardless of reality.

Fifth, humility about what payment reform can achieve. It is a tool, not a solution. It can align incentives, clarify accountability, and improve efficiency at the margins. It cannot create capacity, overcome workforce shortages, or substitute for adequate funding.

None of these requirements is easy to meet. All require political courage, organisational capacity, and a willingness to move more slowly than the political cycle prefers. They require resisting the temptation to oversell reforms, to minimise risks, or to blame implementation failures on lack of enthusiasm rather than design flaws.

And crucially, they require addressing the fundamental drivers of productivity that the NHS Productivity Commission identifies. As the Commission notes: "Productivity is complex, so identifying policy options will take time—and we cannot do it alone."[11] The same applies to payment reform, PFI financing, and governance structures. Complex problems require comprehensive solutions, not isolated fixes.

Who Bears the Risk?

At the heart of all these developments is a question about risk. The NHS is attempting a massive reorganisation of how money flows through the system, at a time when money is scarce and operational pressures are intense. This reorganisation will succeed or fail, will improve care or disrupt it, will create a more sustainable system or accelerate its decline.

Who bears the risk if it goes wrong?

Not the policymakers who designed it. They will have moved on to other roles, other priorities. Not the politicians who approved it. They may not even be in office when the consequences become clear. Not NHS England executives, who will be judged on implementation rather than outcomes and the organisation will cease to exist at that point anyway. Not the banks who extracted billions in profits from PFI deals and will continue to collect their guaranteed returns for decades to come.

The risk falls on trust boards forced to balance impossible budgets, on finance directors pilloried for deficits they cannot avoid, on chief executives managing the fallout from decisions made elsewhere. And ultimately, on patients whose care may be disrupted, delayed, or diminished because the system is too fragile to absorb the shock of rapid change and staff who work in a system they can see ways of improving but are not currently given any meaningful way to do this.

This distribution of risk is not accidental. It is the essence of the accountability shell game. Control is exercised centrally, through payment rules, planning guidance, and regulatory oversight. But responsibility is distributed locally, to organisations that must implement decisions they did not make with resources they did not determine.

When Sir Jim describes the planned changes as "absolutely terrifying," he is acknowledging a truth that is usually left unspoken: this is a high-risk strategy, implemented at the worst possible time, with inadequate safeguards and insufficient resources. It might work. It might not. And if it doesn't, the people who will suffer are not those making the decisions but those living with the consequences.

That IS genuinely terrifying. And it should terrify not just NHS England's chief executive but all of us who depend on the health service, work within it, or care about its future. Because the stakes could not be higher, the margin for error could not be smaller, and the consequences of failure could not be more serious.

The question is not whether change is necessary. It is whether this change, at this pace, with these resources, is wise. And on that question, Mackey's unguarded moment of honesty may be the most valuable contribution to the debate we have had in years.

References

- NHS Confederation. Autumn Budget 2024: what you need to know. October 2024.

- Health Foundation. NHS funding has to translate into improvements the public can see. October 2024.

- The King's Fund. What Does The Autumn Budget 2024 Mean For Health And Care. October 2024.

- HM Treasury. Autumn Budget 2024. October 2024.

- Health Foundation. A budget to stabilise but not yet transform the NHS. October 2024.

- NHS Providers. Briefing on the NHS productivity challenge. 2024.

- NHS England. 2025/26 NHS Payment Scheme – a consultation notice. January 2025.

- NHS England. Revenue finance and contracting guidance for 2025/26. January 2025.

- HM Treasury. Spending Review 2025: Departmental Efficiency Plans. 2025.

- Cook J, de Lacy J, Wood J, Mohammed MA. 10-Year Productivity Forecast for the English NHS: An Expert Elicitation Study. The Strategy Unit, 2025.

- Allas T, Charlesworth A, Chhoa-Howard H, Fozzard K, Moulds A, Rocks S. From diagnosis to delivery: a framework for accelerating NHS productivity growth. Health Foundation, November 2025.

- Darzi A. Independent investigation of the National Health Service in England. UK government, 2024.

- Centre for Health and the Public Interest. P.F.I. Profiting from Inflation? 2023.

- Gaffney D, Pollock AM, Price D, Shaoul J. PFI in the NHS—is there an economic case? BMJ, 1999;319:116-9.

- Patients4NHS. The Private Finance Initiative.

- Scriptonite Daily. All in it Together: How Government Is Handing Ownership of our Schools and Hospitals to Banks. May 2013.

- Novara Media. PFI, the Banks, and the People Uncovering the Biggest Threat to the NHS. April 2015.

- IPPR. NHS hospitals under strain over £80bn PFI bill for just £13bn of actual investment. September 2019.

- Nuffield Trust. Making sense of PFI.

- Centre for Health and the Public Interest. How private finance is crippling health and social care. 2023.

- National Audit Office. Peterborough and Stamford Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. November 2012.

- Department of Health and Social Care. Top NHS trusts given new powers to improve care. UK government, 12 November 2025.

- OECD. Rethinking Health System Performance Assessment. 2024.

- OECD. Health at a Glance 2023. 2023.

This fortnight has had me starting to listen to Influence by Robert Cialdini on audiobook. Its been my way of trying to resist all the marketing guff which gallops into my inbox from Black Friday onwards. There is a real risk of me ordering some absolute nonsense in the small hours whilst feeding the baby.

I've been fluffing around with some Python code to draw together all the Trust and FT accounts for the last 15 years to do some analysis on them.

I'll sign off here and leave you to your mince pies and office parties.

I'll see you in 2026