The Bevan Briefing #5 From DHSC to NHS: Allocation and Funding Flow (and what the new MTPF changes)

Hello pals, thanks for all the comments on the last blog. I’m hoping this one will be similarly instructive.

This issue I’ll be breaking down how the money flows into the system once that global sum has been agreed… and how that changes in the future with the Medium-Term Planning Framework (MTPF) published last week.

Thanks to a readers suggestion, the next installment will be about the different types of contracts for buying healthcare, how they work (or don't) and what happens when there's a bloody big row about who pays for what and a review of the new Strategic Commissioning Framework.

If you have ideas on what to do next then please do contact me....

What follows is the textbook definition of whats supposed to happen. The reality is murkier, with horse trading and bail outs and negotiations. These differ each year depending on the winners and losers.

From DHSC to NHS: allocation and funding flow

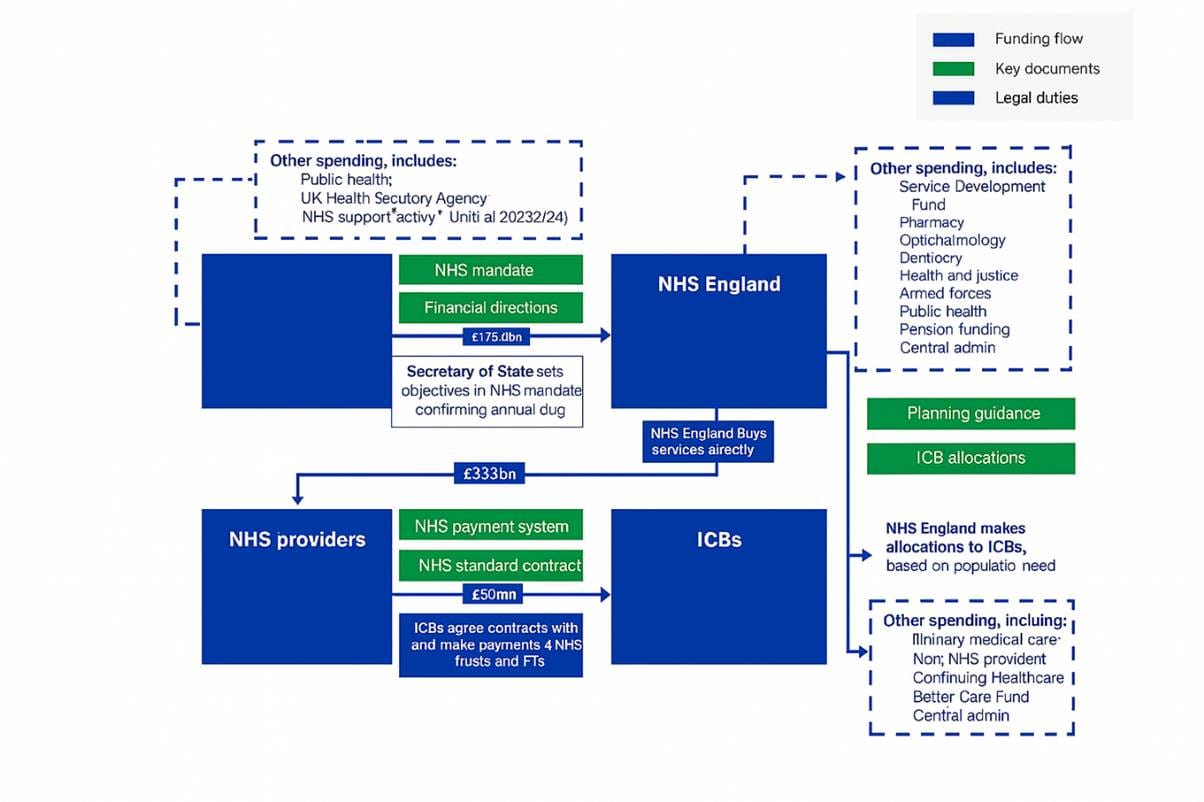

Once DHSC’s overall budget is set, there is a structured process to distribute that money to the front-line health service (primarily the NHS in England) and other health functions. The DHSC allocation is broken down into various components: the largest share for NHS England (currently), portions for public health and prevention, funds for training and other arm’s-length bodies, and a capital budget for infrastructure.

Allocating DHSC’s budget internally. In each year’s DHSC budget, the vast majority of funding flows to NHS England to run the NHS. For example, in 2023–24 DHSC’s total spend was £191.3 billion, of which NHS England received about £180 billion [1]. Through NHS England, funding reaches NHS providers (hospital trusts, GPs, etc.) and pays for services and medicines. DHSC also retains or directs smaller portions of its budget to other areas. In 2023–24, roughly £11.2 billion was spent on “core” departmental activities and public health programmes [1], and about £4.0 billion was passed directly to local authorities – chiefly the Public Health Grant that funds public health services in communities [2][1]. Smaller allocations support DHSC’s arm’s-length bodies (for example, the UK Health Security Agency received ~£2.6 billion for health protection programmes) and other health initiatives [3]. Additionally, a separate Capital DEL is allocated for investment in buildings, equipment and IT. In 2023–24, DHSC and its NHS bodies spent £8.2 billion on capital, funding projects like new hospitals and medical equipment upgrades [1]. (Capital budgets are often earmarked for specific programmes – e.g. the “40 new hospitals” programme (the names are not always that instructive - there are about 2 new hospitals as part of that programme....)– and must be used on investment, not day-to-day operations.) It’s important that DHSC balances these allocations: some funding is ring-fenced for public health or social care grants, and capital is kept distinct from revenue to ensure infrastructure investment isn’t raided for running costs.

DHSC to NHS England via the Mandate. Each financial year, the government sets a Mandate to NHS England, which is the formal policy and funding instruction to the NHS. The Mandate (a requirement under the NHS Act 2006) specifies the NHS England budget for the year and the key objectives NHS England is expected to deliver [4]. For instance, the Mandate will state the revenue resource limit for NHS England – essentially authorising NHS England to spend a certain amount of DHSC’s money – and any capital budget for NHS England. It also lays out priorities (often mirroring Spending Review priorities) such as improving access to GPs, reducing waiting times, etc. In 2025, for example, the Mandate (Road to recovery) set out objectives to cut waiting times, improve primary care access and improve urgent and emergency care, while emphasising that the NHS must stay within its allocated budget and drive efficiency [4][5]. The Secretary of State for Health and Social Care typically issues this mandate (often as a published letter or policy paper) before the start of the financial year. It aligns NHS England’s funding with ministerial priorities – effectively linking money to performance expectations. NHS England is then accountable for meeting these objectives within the budget. This mandate process ensures political oversight: it translates the high-level Spending Review settlement into concrete goals and funding for the NHS.

NHS England’s allocation to Integrated Care Boards (ICBs). NHS England in turn distributes the bulk of funds to local health systems. Since July 2022, England’s health system has been organised into Integrated Care Boards (ICBs), which replaced Clinical Commissioning Groups. NHS England is responsible for determining how much each ICB receives to meet the healthcare needs of its area [6]. This is done through a formula-based allocation to ensure fairness. The core mechanism is the weighted capitation formula, an evidence-based statistical formula that aims to give each area a fair share relative to its population’s needs [6][7]. The principle is to secure “equal opportunity of access for people with equal need” across the country.

How the formula works. It starts with each ICB’s population – but then adjusts (“weights”) that population for factors like age profile, levels of illness and disability, and socio-economic deprivation which affect healthcare need. It also accounts for unavoidable cost differences (for example, areas with higher input costs or sparsely populated rural areas with higher costs per patient), via the Market Forces Factor (MFF) [7][8]. In practice, this means an ICB serving an older or more deprived rural community will get more funding per person than one with a younger urban, healthier population. For example, if two areas each have 1 million residents, but one has a much older population, the formula will weight that area’s population higher, resulting in a larger budget. The compensation for rurality is to offset the costs of suppliers delivering to more isolated areas. This formula is developed with expert advice: the Advisory Committee on Resource Allocation (ACRA) regularly reviews the formula and recommends updates based on the latest data and research [9][10]. The weighted capitation approach has been used since the late 1970s and is refined annually to reflect new evidence and changes (such as explicit health inequalities weightings) [6]. It’s also flawed in places: it uses proxies such as car ownership or employment. That holds across much of the country, but in areas like Chelsea and Westminster people may not own cars because they have chauffeurs, and some don’t work because they have inherited wealth – the formula breaks down at that quantum level. It works for the majority of the population but lumps in the very top with the very bottom of deprivation. That's one of the reasons it gets regularly taken over the coals to see if there's something better out there.

Target and actual allocations. The formula produces a target allocation for each ICB – a calculated fair share of the total NHS pot. However, NHS England usually cannot move directly to those exact amounts in a single year without causing disruption. Some ICBs historically received more than their formula share and some less. To smooth this out, there is a “distance from target” adjustment and gradual convergence. NHS England sets rules for yearly growth to ensure that under-funded ICBs get above-average increases, while over-funded areas get smaller increases, converging toward the fair share over time [7][11]. For example, policy may guarantee that no ICB is more than a set percentage below its target and that all ICBs receive at least a minimum growth each year (to cover fixed costs) [7]. This prevents any area from having a sudden budget cut and allows a steady rebalance to equity. NHS England publishes allocation tables showing each ICB’s actual allocation and how it compares to its target (“distance from target”) [7].

In late December or early January each year, NHS England confirms allocations for the coming financial year (and often for subsequent years). For instance, the allocations for 2025/26 were released along with technical guidance, setting out how the formula was applied (including need indices for different services and explicit health-inequalities weights) [7][8]. The end result is that each ICB knows its budget for commissioning healthcare services for its population.

Other funding streams – primary care and others. In addition to the core ICB allocations for general health services, NHS England also allocates specific funding streams. Notably, primary medical care (GP services) funding is distributed using its own formula known as the Carr-Hill formula (the Global Sum Allocation Formula). Carr-Hill calculates payments to individual GP practices based on the number of patients registered, weighted for factors like age, sex, and certain characteristics that influence consultation workload [12]. Introduced in 2004, Carr-Hill was designed to reflect variations in GP workload and needs – for example, very elderly patients or infants carry more weight, and adjustments are made for things like rurality and patient turnover [13]. Carr-Hill has been criticised for not adequately weighting deprivation (see critique on ICB funding above), and another review of it is underway, with reform proposals expected to ensure areas with greater need get a fairer share [14]. Beyond GP funding, NHS England also allocates money for specialised services (advanced treatments provided in specialist centres) and other specific purposes. These use separate needs-based approaches because not every region hosts services like transplant centres, so funds must follow patients who need those services [7][8]. NHS England’s allocation announcements typically include separate lines for: ICB core services, GP (primary care) allocations, specialised commissioning, and smaller pots like dental or pharmacy services [7].

Carr-Hill has been criticised many times (potted history below...)

- 2007 review (NHS Employers/BMA): recommended using IMD deprivation measures rather than mortality proxies; recommendations not implemented. (NHS Confederation)

- 2015 NHS England review launched to address deprivation/complexity; work acknowledged but no wholesale replacement introduced. (northstaffslmc.co.uk)

- 2016 GP Forward View: publicly stated Carr-Hill was “out of date and needs to be revised”; again, no full formula change ensued. (Health.org.uk)

- 2019–2023 allocations updates: technical guides maintained the existing global sum basis while adjusting other allocations; deprivation concerns persisted in the literature and policy commentary. (NHS England)

- 2024–2025 renewed push: Nuffield Trust and RCGP called for reform; Government (Jun 2025) confirmed a formal review within the 10-Year Plan to ensure “working-class areas get their fair share.” Outcome: review commissioned; changes pending. (Nuffield Trust)

From ICBs to providers

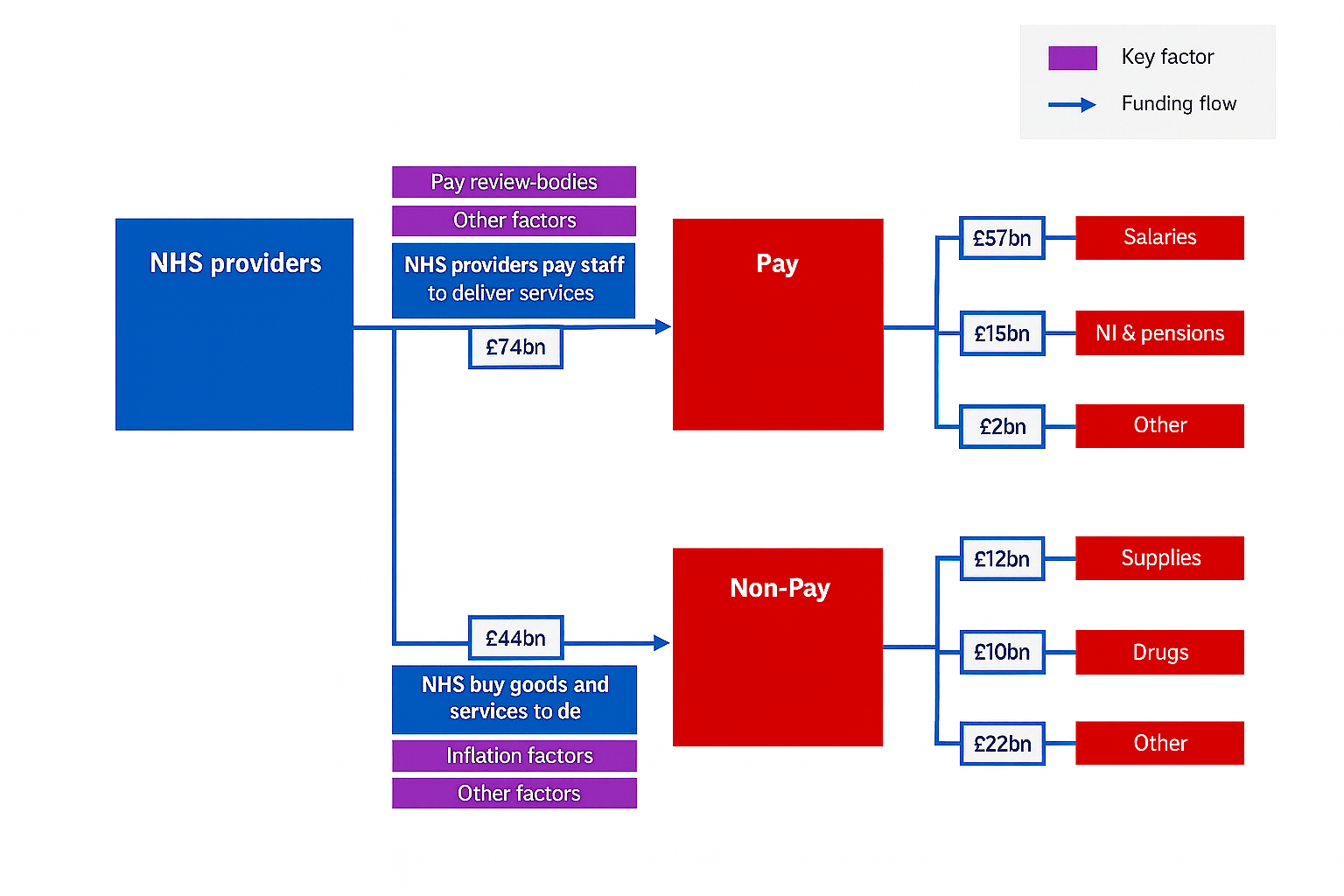

After receiving funds, ICBs (and NHS England for certain direct commissions) then contract with healthcare providers – NHS trusts, hospitals, mental health providers, GPs, etc. – to deliver services. While this explainer focuses on the higher-level allocation, it’s worth noting that ICBs must develop local budgets and plans. They use the funding to set contracts or service level agreements with providers, following national payment frameworks (currently the NHS Payment Scheme, which from 2023 replaced the old tariff system of Payment by Results) [15]. The allocated funds cover things like agreed volumes of hospital activity, primary care services, community care, and so on. ICBs also pool some funds with local authorities for joint health and social care programmes (e.g. the Better Care Fund) [18]. Providers ultimately receive funding via these contracts, and the money flows on a monthly basis for salaries, drugs and patient care. NHS England monitors ICB spending and can intervene if an ICB is overspending or underserving. This ensures funding flows down to front-line care in line with the population’s needs as intended by the allocation formula.

Key points in the annual financial cycle

The process above operates within an annual planning and funding cycle that links government fiscal events to NHS operational planning:

Autumn Budget/Spending Review (Nov/Dec). YOU ARE HERE. In the autumn, the government holds either a multi-year Spending Review or an Autumn Budget/Statement that updates public spending plans. This is when DHSC’s envelope for future years might be confirmed or adjusted. For example, the Autumn Statement 2022 (amid high inflation) topped up the NHS budget by an extra £3.3 billion in each of the next two years [20]. Typically by late November or December, the NHS knows its expected funding for the next financial year (and often an indication for years ahead). If an Autumn Statement follows a previous multi-year settlement, it usually confirms the next year’s funding or makes tweaks in light of new pressures. These late-year Treasury decisions set the stage for NHS planning.

Mandate and Planning Guidance (Dec–Jan). Following the fiscal update, the DHSC issues the NHS Mandate (as described above) – in recent years around December or January for the upcoming year. In parallel, NHS England releases its annual Planning Guidance. The operational planning guidance (usually just before or after New Year) translates the mandate and budget into detailed priorities and rules for local NHS bodies [4][5]. For example, the 2025/26 Planning Guidance, aligned with the government’s mandate, focused on a few national priorities (improving access, productivity and financial balance) and gave systems flexibility in using funds. The guidance specifies targets (e.g. elective recovery trajectories, A&E wait standards), policy requirements, and the financial framework for the year. It also includes technical financial instructions – such as efficiency assumptions, rules on carry-over of funds, and business rules for ICBs (for instance, limits on administrative spending or requirements to break even) [16]. At the same time, NHS England publishes the allocations for each ICB and supporting materials like formula explanations [7][8]. In effect, by early January the NHS at every level knows how much money it will have and what it needs to deliver.

Local planning (Jan–Mar). With the guidance and budgets in hand, ICBs and NHS providers enter a period of detailed planning and contracting. They draw up operational plans showing how they will deploy the funding to meet activity targets and patient needs. There is often an iterative process where ICBs submit draft plans to NHS England, which are reviewed and adjusted to ensure they are realistic and on target. I am aware that those of you who have done this before are laughing at this statement but its a reminder of how the system is designed to run. Without recourse to personalities, competence or the sheer workload of prepping for year end / audit / trying to spend the bung you got on 1 March to be spent by 31 March ensuring tax payers value for money but with very little wiggle room....

Contract negotiations between ICBs and hospital trusts (or other providers) typically conclude by the end of March so that services can continue smoothly into the new year. This period also involves finalising any specific initiatives (e.g. service expansions funded by targeted pots). By the end of March, the NHS has an agreed plan and budget for the year for each area and provider. This is also where there is often a set of funds moved around based on capital underspends for major projects. This money is often shuttled to ICBs and Trusts with little notice but with some sizable restrictions on spending.

Start of financial year (April) and in-year monitoring. The new financial year begins on 1 April. NHS England formally delegates budgets to ICBs (and its own direct commissioning teams) as per the allocations. Throughout the year, there are checkpoints – for example, Q1/Q2 operational reviews, and an annual mandate review where the Health Secretary checks progress against the objectives. Funding can sometimes be adjusted at the margins in-year: for instance, if additional funds are released (say, a Spring Budget might inject some extra money for winter pressures or a new vaccine programme), DHSC will distribute that to NHS England or ICBs as appropriate. Major re-openings of budgets mid-year are rare; generally the task is to manage within the set allocation. The DHSC and Treasury monitor spending via monthly financial reports to ensure the NHS does not overspend its DEL [21]. If an Autumn Statement or emergency budget occurs mid-year, it usually influences the following year’s plans rather than the current year, except in urgent scenarios.

Autumn/winter (year-end). As the cycle continues, by the autumn the Treasury and DHSC are already looking ahead to the next year(s). If it’s a Spending Review year, a new multi-year deal will be negotiated (as discussed in last week’s blog). If not, the autumn budget will confirm the next year’s figures. The House of Commons also scrutinises DHSC’s spending twice a year via the Estimates process (Main Estimates in spring and Supplementary Estimates in late winter) – this is where the agreed funding is formally authorised and any adjustments (like reserve funding for a crisis) are approved [22][23]. While technical, these parliamentary steps are key points where the allocation is finalised. The cycle then repeats with the mandate and planning for the next year. Alongside this, NHS England runs the Performance Assessment Framework for ICBs and providers, segmenting systems and setting out intervention expectations where needed [24].

Last week’s MTPF: what’s new?

Last week NHS England published its first Medium-Term Planning Framework (MTPF) covering 2026/27–2028/29. Building on the 10-Year Health Plan, it uses the new three-year funding settlement to shift from one-year to multi-year financial planning. The MTPF is explicit that all ICBs and trusts must prepare long-range plans (five-year strategies with three-year detailed returns) and deliver balanced budgets in every financial year. To support this, capital allocations and revised technical guidance (including new delegated limits and business case templates) are being released alongside the framework [5][16].

Key financial requirements. The framework is designed to embed strict financial discipline. Every ICB and provider must produce multi-year plans and achieve break-even (or surplus) without routine deficit support by the end of 2028/29. Plans are explicitly required to incorporate at least 2% year-on-year productivity improvements. At the same time NHS England will continue moving ICB allocations toward a “fair shares” model, phasing out ad-hoc top-ups (like elective recovery or deficit support funding) and reviewing the national funding formula and GP Carr-Hill formula. These steps aim to make budgets more transparent and equitable. For example, the framework notes that “ICB allocations will move toward the fair sharing of resources” and that remaining deficit-support mechanisms should be unwound (with any use of deficit funding reported openly to boards). In practice, this means systems will bear more of the financial risk (and reward) of performance [5][16].

Payment mechanism reforms

The MTPF signals a major change in how providers get paid. Most notably, NHS England plans to phase out traditional block contracts in favour of activity-based and blended payments. Under the new approach, urgent and emergency care (UEC) will be paid by a hybrid model: from 2026/27 trusts will receive a fixed budget (price×activity) plus a variable payment worth 20% of income. This split payment is intended to better align incentives – rewarding efficiency and channelling resources into community care as acute demand falls. In parallel, NHS England is developing an “incentive element” of the UEC model (co-designed with clinicians and managers) to encourage right-care improvements [16].

At the same time, the standard NHS Payment Scheme (the system of national tariffs) will be revamped. The MTPF promises new “best-practice” tariffs from 2026/27 designed to encourage more day-case and outpatient care and the use of technology in treatment. These tariffs emerge from pilots and consultations on procedures that could safely move out of inpatient settings (“Right Procedure, Right Place”), meaning that price incentives will explicitly favour the quickest, most efficient pathways. Block contracts will give way to these dynamic payment schemes, so that most funding flows through the tariff and its successors, with only limited “blended” contracts where necessary [15][16].

- UEC payments: New model (fixed price + 20% variable) from 2026/27; incentive add-ons to be co-designed.

- Tariffs and activity: A refreshed Payment Scheme in 2026/27 will introduce best-practice tariffs to shift activity towards day-cases, outpatient and tech-enabled care.

- Block contracts: Providers will gradually move away from large annual block budgets, dismantling block elements in favour of outcome-linked and activity-based deals.

- Neighbourhood incentives: As acute demand falls, a companion model will unlock funding for neighbourhood health – a separate scheme is being developed with pilot sites to feed savings into community services from 2026/27.

Overall, payment reforms are intended to realign incentives across providers. By combining fixed and variable fees and reshaping tariffs, NHS England aims to reward productivity and prevention. The framework also underlines more transparent data use: routine publication of trust-level productivity statistics and unified costing dashboards will support this new regime [16].

Integrated Care System (ICS) planning and budgets

The framework deepens the role of ICSs (ICBs) as strategic commissioners. For the first time, ICSs must produce fully-integrated multi-year plans covering finance, workforce and activity. The 10-Year Plan requirement for five-year strategic plans is reaffirmed: every system should submit a five-year narrative and detailed three-year numeric returns for 2026–29. Regional teams will review draft plans and work with ICBs to refine them before final approval [5].

To underpin system-led planning, ICBs will receive more predictable multi-year allocations. NHS England says the Spending Review settlement provides roughly +3.0% real-terms per-year revenue growth (and +3.2% capital) over the period. Capital allocations will be announced in autumn 2025, and new devolved limits will let ICBs retain underspends within the system [5]. In effect, ICSs and trusts now share a common budget envelope. ICBs must ensure their five-year plans meet national priorities (the “three shifts” and 15 success measures) while balancing their books each year.

This marks a departure from the previous model of annual contracts and trust-level targets. NHS England has consulted on letting ICBs take on traditional GP screening/vaccination commissioning (from 2027) and is updating its strategic commissioning framework for NHS services. New contract archetypes – single-neighbourhood, multi-neighbourhood, and Integrated Health Organisation (IHO) contracts – are under development. IHOs in particular are envisaged as capitated contracts (not new legal entities) that take responsibility for a defined population’s health. Crucially, IHO contracts are expected to work with the wider provider landscape via sub-contracting and delegated commissioning. In practice, this means systems can pool funding and redistribute it across hospitals, community and independent providers under a single contract structure [16].

Risk-sharing and performance incentives

With the dismantling of short-term top-up payments, financial risk and reward will fall more clearly on local systems. The MTPF makes clear that in-year pressures must be managed locally. Boards are now expected to include a formal risk assessment in their planning submissions, and any reliance on central support must be minimised. If a deficit-support fund is in place, only the remaining underlying (non-DSF) financial position is counted. In effect, ICSs must plan to live within their means and identify contingency actions for any unforeseen cost pressures [5][16].

While the framework does not explicitly revive national “gain-share” rules, its logic is similar. Systems meeting or beating their targets (e.g. waiting lists) can keep savings to invest in local priorities (such as expanding neighbourhood care), whereas failure to hit plans will tighten future allocations. The focus is on mutual accountability: financial surpluses must be reinvested in agreed priorities, and overspends cannot simply be bailed out. This is reinforced by the updated oversight regime, which will expand metrics to include system-level outcomes and use performance-driven intervention rather than arbitrary cuts [24].

Independent sector and contracting

The MTPF does not specifically single out independent providers, but its reforms will affect their role. Under the new models, capacity purchased from non-NHS providers (for example, elective surgery) will need to fit into multi-year, outcomes-based contracts. In practice, this means that independent sector arrangements will likely be negotiated within the ICB’s overall budget plan or as sub-contracts of integrated providers, rather than as separate one-year block agreements. For example, an Integrated Health Organisation holding a capitated contract could sub-contract some elective work to independent hospitals if that is the most efficient way to meet targets. The national tariff still applies to independent activity, but future deals will need to align with the ICB’s Payment Scheme and integrated care objectives (e.g. reducing system cost by shifting care out of hospital) [15][16].

Capital, innovation and contractual terms

Finally, the framework ties capital planning to this new operating model. NHS England promises a reformed capital regime to get better value from public and private investment. This includes releasing multi-year capital allocations and clear delegated limits so that ICBs can embed infrastructure projects (like new neighbourhood health centres or digital platforms) into their five-year plans. Future contracts may include explicit capital commitments or estates plans – for example, allocating funding for joint-use community hubs under a neighbourhood contract [5][16].

Innovation is woven into the planning guidance through technology and prevention priorities. For instance, the framework urges a shift to digital-first urgent care (expanding telephony triage and same-day booking) and to remote/digital outpatient models. Though it doesn’t spell out new budgets, the implication is that providers will need to invest in innovation (digital pathways, AI triage, etc.) as part of their productivity improvements. Some of this may be funded through capital or transformation funds (now to be accounted for in multi-year plans), while contract payments will increasingly reward innovative practices [5][16].

Performance management

There is a difference between what a document sets out as intention and actually ushering that into being. The wish for a set of balanced budgets and credible plans – against the backdrop of funding constraints – does not make it so. More money has gone in, and yet productivity has dropped. How the circle will be squared with a longer roadmap and inadequate funding is not clear.

In summary, the 2026–29 framework signals a major overhaul of NHS finance and contracts. With an underlying assumption of adequate capital and revenue for providers, it ushers in multi-year, integrated system budgets, new blended payment models (especially for urgent care), and tighter financial accountability for ICBs. Although many technical details will come in the accompanying guidance, the direction is clear: more flexible, incentive-driven contracts (with block budgets largely phased out) and far stricter planning rules. Systems and providers will need to collaborate closely, harness data and innovation, and plan at scale if they are to meet the new targets and financial tests.

References

- DHSC. Annual Report and Accounts 2023–24 (web accessible PDF). https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/676150ef26a2d1ff18253415/dhsc-annual-report-and-accounts-2023-2024-web-accessible.pdf

- DHSC. Public health grants to local authorities: 2025 to 2026 (allocations & circulars). https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/public-health-grants-to-local-authorities-2025-to-2026

- UKHSA. Annual report and accounts: 2023 to 2024 (landing). https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/ukhsa-annual-report-and-accounts-2023-to-2024

- GOV.UK / DHSC. Road to recovery: the government’s 2025 mandate to NHS England. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/road-to-recovery-the-governments-2025-mandate-to-nhs-england

- NHS England. 2025/26 priorities and operational planning guidance. https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/2025-26-priorities-and-operational-planning-guidance/

- House of Commons Library. NHS integrated care board (ICB) funding in England (Briefing CBP-10031). https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-10031/

- NHS England. Allocations hub (ICB allocations, technical guides, spreadsheets). https://www.england.nhs.uk/allocations/

- NHS England. Technical guide to allocation formulae and convergence for 2025/26 revenue allocations (PDF). https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/PRN01601-technical-guide-to-allocation-formulae-and-convergence-for-2025-to-2026-revenue-allocations.pdf

- DHSC. Advisory Committee on Resource Allocation (ACRA) – information (PDF). https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/68de6d8cdadf7616351e4d5a/ACRA-member-candidate-information-pack-final.pdf

- GOV.UK. NHS resource allocation formula: ACRA advice and SoS response (historical context). https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/nhs-resource-allocation-formula

- HFMA. NHS allocations to ICBs – overview slides (method and indices) (PDF). https://www.hfma.org.uk/system/files?file=230703—nhs-allocations-to-icbs—slides.pdf

- BMA. Global Sum Allocation (Carr-Hill) Formula – overview and factors. https://www.bma.org.uk/advice-and-support/gp-practices/funding-and-contracts/global-sum-allocation-formula

- North Staffordshire LMC. Focus on the Global Sum Allocation Formula (Carr-Hill) – explainer (PDF). https://www.northstaffslmc.co.uk/website/LMC001/files/Focus-on-the-Global-Sum-Allocation-Formula-July-2015.pdf

- Kent County Council (HOSC). Carr-Hill Formula – briefing (2025) (PDF). https://democracy.kent.gov.uk/documents/s131229/Item%206%20-%20Carr-Hill%20Formula.pdf

- NHS England. NHS Payment Scheme – landing page (2025/26 materials). https://www.england.nhs.uk/pay-syst/nhs-payment-scheme/

- NHS England. Revenue finance and contracting guidance for 2025/26 (long read). https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/revenue-finance-and-contracting-guidance-for-2025-26/

- NHS England. The NHS Performance Assessment Framework for 2025/26 (ICB/provider segmentation). https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/the-nhs-performance-assessment-framework-for-2025-26/

- DHSC / DLUHC / NHSE. Better Care Fund policy framework: 2025 to 2026. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/better-care-fund-policy-framework-2025-to-2026/better-care-fund-policy-framework-2025-to-2026

- Health Foundation. Spending Review 2021: what it means for health and social care. https://www.health.org.uk/reports-and-analysis/analysis/spending-review-2021-what-it-means-for-health-and-social-care

- NHS Confederation. Autumn Statement 2022 – what you need to know. https://www.nhsconfed.org/publications/autumn-statement-2022

- HM Treasury. Managing Public Money (2025 edition) (PDF). https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/684ae4c6f7c9feb9b0413804/Managing_Public_Money.pdf

- HM Treasury. Main Estimates – collection. https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/hmt-main-estimates

- HM Treasury. Supplementary Estimates 2024–25 – collection. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/supplementary-estimates-2024-25

This fortnight I have been mostly

Reading the little guides sent out by the good people at Kaleidoscope Health and Care especially the one on delivering the 10 year plan. They were key to running a bunch of the deliberation events so have the inside track.

Lots of helpful reminders of doing things with people and not to them, messages which feel like they are falling on deaf ears at the department. We are sadly seeing a resurgence in the management style of Milburn which is 'the beatings will continue until morale improves'.

Listening to the latest (albeit 2022) offer from Tom Vek https://open.spotify.com/album/0jqFy88GjNeqFZGu7VwgL5?si=gCRrY2zCRLGHvtRqXxL4wQ

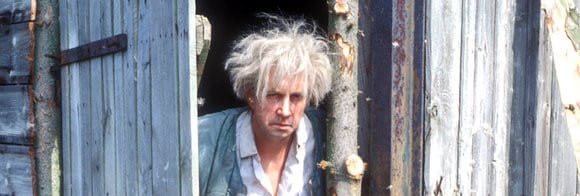

And enjoying the Slow Horses finale - I wish I were a Jackson Lamb type although I already have the glasses. Just the dirty trench coat and manky shirt to go to complete the look. Some days in the post partum trenches I am probably closer to the oeuvre than I'd care to admit....

Go well pals, and let me know what else you'd find useful for me to cover next.